Don't Upset ooMalume: A Guide to Stepping Up Your Xhosa Game

Nqandeka writes with an easy familiarity of the Xhosa cultural background showing how the ordinary

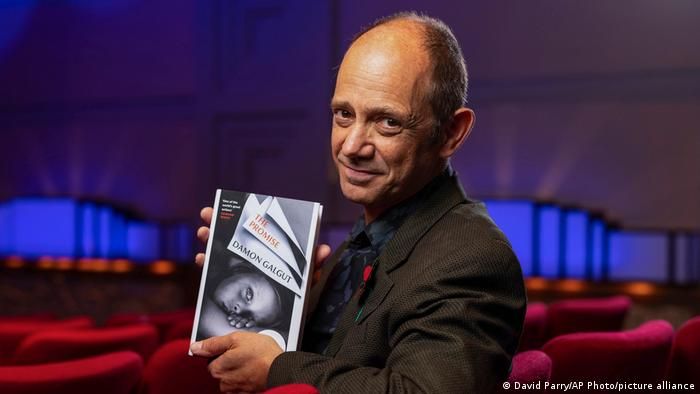

The Manbooker Prize has long been coming for Damon Galgut since 2003 when his book, The Good Doctor, was shortlisted. In 2010 I certainly thought his shortlisted book, In A Strange Room, should have definitely won. I had low expectations this time around but it was a wonderful surprise when The Promise won.

I was lucky enough to record an Open Book Podcast, which will be released on the 19th November 2021, with Futhi Ntshingila and Damon Galgut a few weeks ago. The organisers had sent us each other books to read for preparation. What became clear to me in all three books is that here were some contemporary South African writers, of more or less the same age, from different backgrounds, struggling to exorcise the ghosts of the country's recent history. Having been born at the height of apartheid era and becoming adults during the threshold of our country's democratic freedom, history imposed itself on our generation, and here we were wrestling with it in a language of hunger, longing and unfulfillment.

Ntshingila's They Got To You Too, tells a story of a retired Afrikaner army general who had opportunistically managed to maintain his position on the new South African dispensation through born-again politics of serving the new black political masters. Dying he's now being cared for by a black nurse who had felt left behind when her comrades went to exile after witnessing the killing of their school political activist mate. They get into a strange relationship of trust through telling each other stories of their past.

Galgut, in The Promise, uses four funerals to laser examine, in a semi caricature manner, the mores and the zeitgeist of an Afrikaner family over forty years. We're taken into the shifting political sphere of South African politics. In this book of sometimes dizzying narrative voices you can't help notice that Galgut is striving for a fresh language to express the prevailing sense of South African socioeconomic tragic strandedness. The book is heavily themed on Whiteness, the angst of the previously privileged post apartheid era and their anxieties of feeling out of place in the new dispensation.

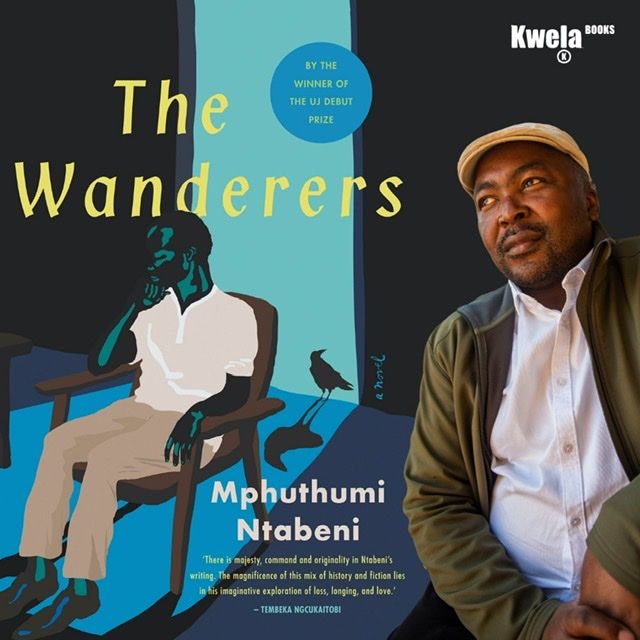

My book, The Wanderers, is more Pan-Africanist in sense that its three major setting are South Africa from the late eighties to 2019, Rwanda during the genocide period of 1994, and Tanzania where my South African born protagonist dies at the turn of the millennium. It also follows Susan Sontag's notion of our bodies talking louder and clearer to us in sickness since one of its protagonist writes a journal on the grave mouth, dying from Aids in 1999.

The running thread of these books can be summarised as: Grinding personal and national disillusionment; the investigation into the instability and unpredictable shifts of personal and national identity; deriving creative energy from ingesting psychological insights into historical and cultural events.

The Promise in particular demonstrates the complicity of those who have had a privilege to look away when others were being oppressed, gagged and imprisoned. Those who are shackled within the schizophrenia of their own culture and worldview. Even post apartheid this self imposed deafness is still their ethical response and tactic for maintaining, at all costs, their slowly fading privilege. Galgut goes for the jugular, choosing tragic comedy to cartoon the self imposing protective amnesia that's too blind to see. This enabled him to eviscerate their false innocence without appearing too judgemental. Whereas Ntshingila chose to ride on the spirit of limitless hope and deep empathy in dealing with post apartheid Whiteness anxieties, emphasising more the possibilities of black and white reconciliation. I aimed at depicting the invading absurdity in our national and personal lives whose roots are deep in our tragic history. To showcase also what Thomas Mann called the 'heart asthma of exile' in interrogating what it means to be homeless, even lost, when you no longer want to be found.

If art is the most personal way of engaging history these three books throw a writing thermostat into the seethings sociopolitical aspects of South African history to see if the fund of our hope is still valid and serving the dreams of freedom as envisaged in the 1994 promise of its democratic dispensation. What is clear from the books is that South Africa is on Gramsci's interregnum moment when the old refuses to die while the new is being born. This brings with it a terrible national and personal anguish. The books look at this from different races, cultures and class. They examine South Africa's inability to make sense of her never fully acknowledged past atrocities, much less atoned for, as perhaps something behind the current rise to her new sociopolitical and economic strains. They ask if perhaps this is not what is at the centre of the country's misdirection and disenchantment.

Albert Camus was of the opinion that during the last hour of a dying order, which is usually the height of its hubris, history tends to put on the mask of destiny and forces its people to live in a climate of tragedy. This is where South Africa is at the moment with the pendulum swinging between two poles: invading nihilism and limitless hope.