BLACK HELEN OF TROY

If true the casting of a Black woman, Lupita Nyong’o, by the director Christopher

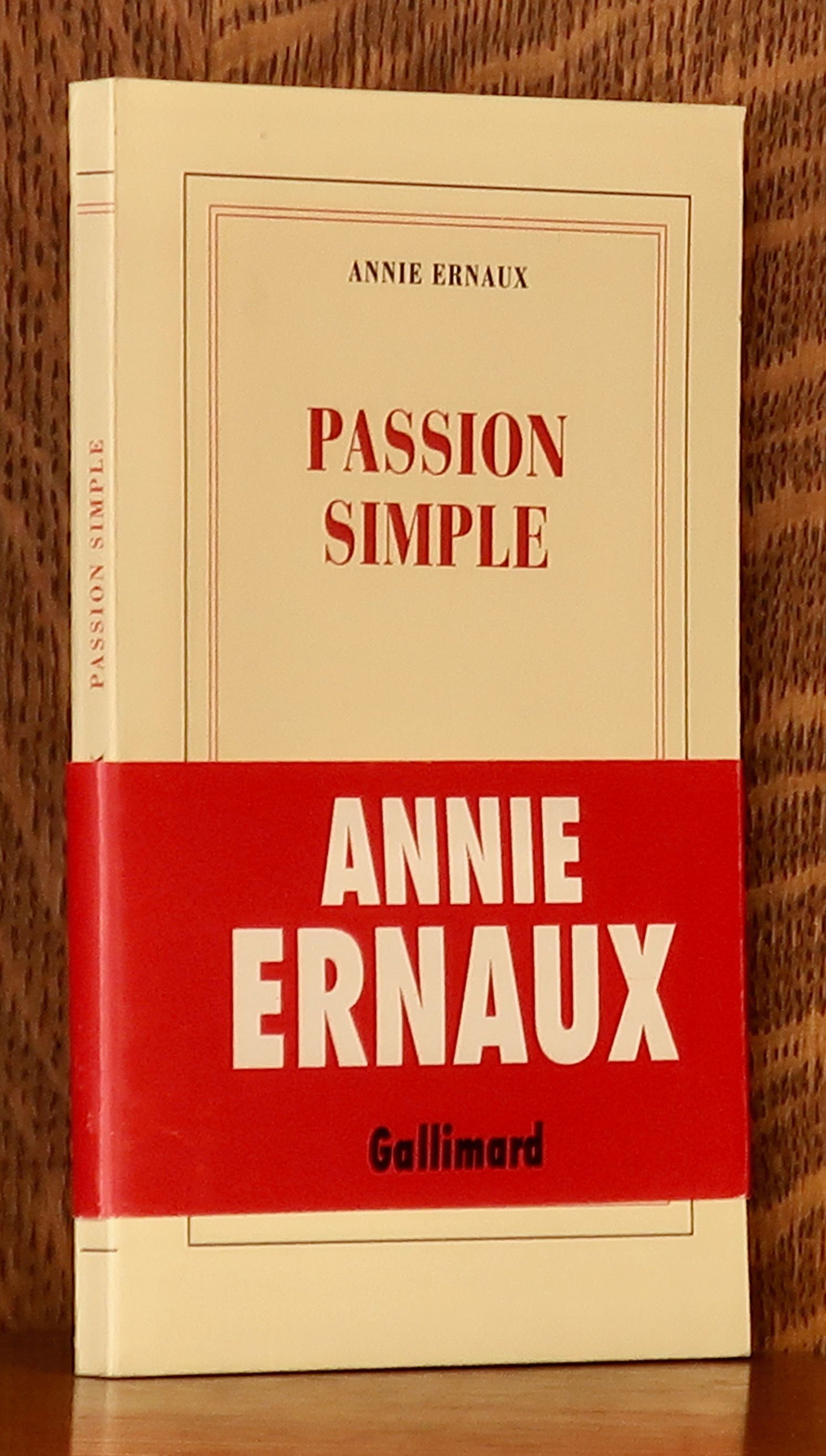

An intellectually bent woman records her descent into passion through a brief period when she was consumed by an affair with a married man of foreign culture to hers. Through it she discovers that romance is more obscene than sexual deviation, this being the epigraphic quote of Marquis de Sade the book begins with. She spends almost all her time, 'bursting with frenzied energy,' while waiting for his phone call to arrange their sexual encounter. Time spent away from him feels like her body is floating into herself. Time spent with him bring apprehension that “touching and pleasure would eventually draw us apart. We were burning up a capital of desire. What we gained in physical intensity we lost in time.” All of a sudden, Time, the measure by which our bodies age by no longer feels intangible, but is transformed into physical sense that makes her participate in the world in a much more physical and real way.

Naturally, in the listing and description of these facts, there is no irony or derision, which are ways of telling things to people or to oneself after the event, and not experiencing them at the time.

Taking a pointer from a first porn movie she ever watched the pratagonist takes an idea: “It occurred to me that writing should also aim for that—the impression conveyed by sexual intercourse, a feeling of anxiety and stupefaction, a suspension of moral judgment.”

She even sums the thesis of the book as she writes about the affair:

I discovered what people are capable of, in other words, anything: sublime or deadly desires, lack of dignity, attitudes and beliefs I had found absurd in others until I myself turned to them. Without knowing it, he brought me closer to the world.

There is so much more she learns about her self through this all consuming passion about this man in the course of few years, especially about ways we cheat by lending intellectual strength to our physical desires and biases when we are consumed by them. More than that, the book is about showing how our physical desires bring us back to the world and take us a peg or two down from our intellectual cuckoo lands. The resigned tone says it all: I thought to myself with surprise, “I’ve come round to this too.”

When he goes back to his country, ceasing all communication with her, she takes up a pen, not as means of easing her sense of grief, but as a way of capturing "…something imperishable that cannot be conveyed by memories … " In the end, she doesn't feel she has betrayed either him or herself theough unhealthy exhibitionism by writing the book:

All I have done is translate into words—words he will probably never read; they are not intended for him—the way in which his existence has affected my life.

He comes back after a year of her tortured anticipation. As usual, he phones to arrange their sexual encounter, she agrees, but:

The man who returned that evening wasn’t the man I was carrying inside me throughout the year when he was here, and when I was writing about him. I shall never see that man again.

The spell has been broken.

This beautifully written book tells as means of evoking real emotions beyond the theories and jargon of moralism. It'll teach you more in fifty pages about passion, loss of self-restraint, and meaninglessness of visiting passions than any ideology will confuse you in fifty volumes. And like the protagonist it might bring you uncomfortably closer to your carnal weaknesses than you could have imagined in a million years. And, with any luck, even smuggle some dreamed of passion back into your dry veins.