Don't Upset ooMalume: A Guide to Stepping Up Your Xhosa Game

Nqandeka writes with an easy familiarity of the Xhosa cultural background showing how the ordinary

I often have a problem with 'big issues' novels who derive their themes from the cacophony of the crowd. Not that I'm against novels that tackle pressing issues of the times. But often this is done in a non nuanced reportage manner, without investing artistic narrative into the writing, thus end up being preachy, pummeling us with undigested presentation of these issues without the required psychological acumen and other requirements of good artistic presentation.

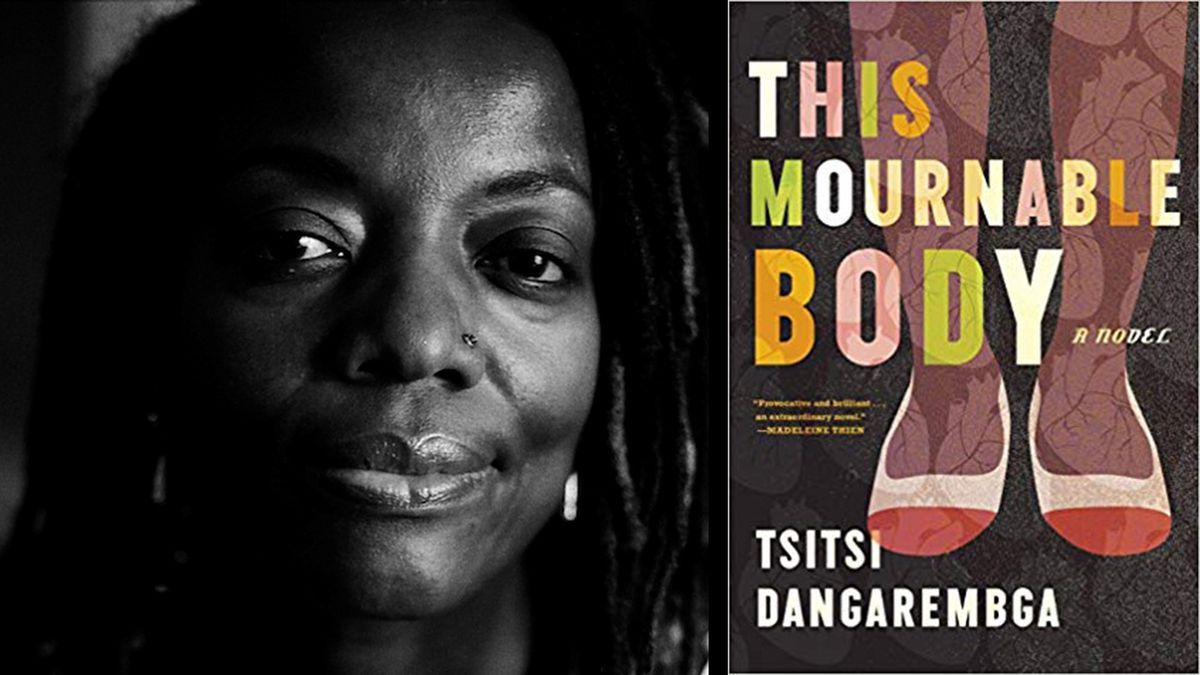

I was glad to discover that The Mournable Body, though it touches many big issues of our era does so in subtler ways, discussing them as reactions (mostly in inner stream of consciousness) of characters to the nature of things. Though this novel is a biting narrative against the post colonial quandaries of the Zimbabwean situation (the disorder and disintegration, the oppressive consequences of empty rhetoric of African particularism, aggressive localism and impotent nationalism) it is not overtly political. Dangarembga here is telling a human story, what happens to individual lives when things fall apart and the fish rots from the head. She delineates how the sociopolitical failing condition infiltrates and saps personal lives. How the national and personal socioeconomic dilemma makes the country and individuals into liminal figures she depicts in the haunting character of Tambudzai Sigauke.

We first met the protagonist, Tambudzai, as a feisty by jovial girl child in The Nervous Condition, itself a sweeping exploration of sociohistorical background that made for Zimbabwean early independence era. The Nervous Condition is more optimistic and brighter book that reveals the intertwining roots of generalized dispossession and colonialism. In this third book of the trilogy (I'm still to read the second book, The Book of Not) Tambudzai is all grown up, educated and psychologically disintegrating through her seams. Her voice, still brilliantly observant about the going ons around her, has acquired a melancholy tinge from being dogged by the spirit of Mephistopheles she calls the ants crawling within her skin:

You grow thinner, and do not know whether to be pleased about this or not. There is a dullness to your skin, like a thin membrane enveloping despair. It tells people you have collided with your limit; you do not want them to know this.

She calls ambition a ravenous hyena, and hunger and poverty a blade toothed rodent.

Tambudzai's problems are myriad but boil down to having to contend with: unemployment, classicism, racism, gender violence, socioeconomic collapse, social and political betrayal of the national nightmare that is the state of Zimbabwe during the turn of the millennium. Because she's educated and still relatively young she is confounded by her reluctance to leave the country, like the rest of her friends and family some of whom she even envies. Her cousin who emigrated to German gets a frequent mention, and in the end is the one who bails her out when she ends up on a mental hospital. This sums her mental musings about the issue:

If you cannot build a life in your own country, how will you do so in another?” These are the questions that runs through her own mind.

When as a last option Tambudzai takes a teaching job the principal rubs the salt on her wound by telling her in no uncertain terms that her degree is a wrong one for the required subject. As if reading her mind the principal also wonders why as young woman Tambudzai has not chosen to immigrate. She confounds her humiliation by asking:

Are we to commend your patriotism or deplore a certain lack of initiative?

Through subtler ways like these Dangaremba gently slips in by the back door pertinet questions about one's responsibility to the country, even a failing one. She skillfully skirts and negotiates through the character of Tambudzai and her cousin this question of whether the Zimbabweans who choose to escape the national implosion of their country are reprehensible or have more sense. Recognizing the pointlessness of getting trapped on such binary thinking about those who left and those left behind, she doesn't nail her colours on the mast. Bt the point she's trying to make, I assume, is that not all those who stay are merely stranded, it is mucch more complicated than that. Perhaps they stay, like herself, because they recognize that their duty is best served at staying than leaving. She brilliantly proffers no opinions about those who leave/left.

Tambudzai also doesn't have a very good relation with other women in her life: mother, mates or elder sisters, some of whom have questionable psychological balance that's complicated by the fact that they're returning women of war with strong bonds among themselves that exclude and find others suspicious. She also feels a nagging guilt because she got and chose the scholarship to a prestigious multiracial college in Umtali, the Young Ladies’ College of the Sacred Heart when others were going to war to fight liberate their country. As such, though her sisters, they treat her like a stranger. In some complicated way she also doesn't want or fake being part of them either. This is a passage when Christine, a family friend, who went to war with her Tambudzai's sister comes visiting, bringing with her a bag of maize meal for sadza from her mother who want to make sure her unemployed daughter doesn't starve. Tambudzai carries this bag from house to house she resides on as an albatross of humiliation around her neck:

“We were taught not to be selfish during the war,” continues Christine, who up until this evening had not displayed much interest in conversation. “Because then everyone dies. There was a boy I liked. They kept on sending him up to the front until he was killed. I thought even then, that’s selfishness. In spite of what they taught us. Even though we fought the war, it was full of liars.” It is now too late to begin the conversation you should have had weeks ago, when Christine came, concerning your family and their need and your inability to do anything about those needs because of your city poverty. Christine has that layer under her skin that cuts off her outside from her inside and allows no communication between the person she once believed she could be and the person she has in fact become. The one does not acknowledge the other’s existence. The women from war are like that, a new kind of being that no one knew before, not exactly male but no longer female. It is rumoured the blood stopped flowing to their wombs the first time they killed a person. People whisper that the unspeakable acts were even more iniquitous when performed by women, so that the ancestors tied up the nation’s prosperity in repugnance at the awfulness of it, just as they had done to the women’s wombs. It occurs to you that you are more like Christine than you are like Mai Manyanga: Christine with her fruitless war that brought nothing but false hope and a fresh, more complete variety of discouragement. You with your worthless education intensifying your beggary, making it all the more ludicrous.

At the school where she taught things starts to unravel for the worst and Tambudzai ends up being admitted at a mental hospital for months. She's eventually rescued by her returning cousin from Germany with a Deutsch husband. She stays with them, admiring the tranquility of their lives, until she finds another gainful employment from her former white classmate who by then owned her own company of environmental tourism. The cousin's husband is in the country on the PhD research pretensions. He says:

It is true, there is too much that is wrong. At the same time too many are too happy to keep saying what is wrong. Not enough see what is right also. I am thinking I will look at the imagery in Zimbabwean stone sculpture instead of images of death. Do you know that five of the top ten stone sculptors in the world are Zimbabwean?

From this Tambudzai gets a clue about promoting what is positive about her country, showcasing their culture that goes to ancient of days regarding golden sculptures and all. For instance, some historians believe the so called Chobona people Jan van Riebeeck mentions in 1657 diary about what he heard from Eva that the Khoe traded with for gold and cattle were actually from Zimbabwe than the Xhosas. Tambudzai finds her niche that gives her a final break at work. Eventually she's promoted to being in charge of this village tourism division. Complication develop again when she tries to bring the tourists to her own village where her mother is in the management of a powerful Women's Club. She has to pay bribes to the village management and war veterans, including her own sister, for the project to go ahead. Things fall apart on the first visit of foreign tourists and Tammbudzai is forced to tender her resignation. The book ends on a bleak note:

They do not know what it is to struggle with the prospect that the hyena is you, nor how this combat marshals in the task of finishing the brutish animal off, while ensuring you remain alive yourself. You squash an ant scuttling over the table and raise your finger to inspect its crushed black body, but your finger is clean.

This is a book of personal slow suffocation from deepening loneliness, lack of enterprise and the limiting and frustrating political obtuseness that makes individuals to be haplessness despairing because of dearth of national vision. It shows in lived lives the collapse of liberation movement and the failure of aspirations and ideals promulgated by Frantz Fanon as need for post colonial nations to “…turn over a new leaf…work out new concepts, and try to set afoot a new man.” The postcolonial African new man is failing to emerge, and in this period of darkening interregnum, where in the prophetic words of Antonio Gramsci, the old is refusing to die to allow the new to be born. Because of all of this the African individual in our era is either crucified, like Tambudzai, or scattered as an immigrant in the diaspora like her cousin. African goverments shoulder the greater blame for this inability to bring to flower the gains of our freedom.

Our national independences were not just about the transfer of political power, an exchange of the elites where, in Orwellian language, the pigs grow human faces. But almost everywhere in Africa, including Zimbabwe and South Africa, this has become the case. Zimbabwe, because it got its independence first, is just ahead of South Africa in this state of decay. Our national liberation movements have failed to inspire and facilitate a new culture of socioeconomic development. To maintain, develop and fairly redistribute the state of the existing infrastructures from cruel colonial rule that excluded the majority black. They've failed in nurturing homegrown intelligentsias for the organization of new social data that is required for Africa to competently prosper in the 21st century despite the empty rhetoric of Fourth Revolutions and all. The replacement of the ballot system with state violence is the only end for failing governments as Dangarembga herself is finding out from personal experience of being arrested for peaceful demonstrations against state corruption.

Governments alone, of course, cannot resolve the dilemmas of our postcolonial quandaries. But the least they can do is to promulgate and facilitate means for personal and private company economic transformation. But ours are fast becoming mimic men of the colonial system they supposed to have liberated us from. They are maintaining apartheid social and economic exclusion of the majority black, the apartheid geography of settlement in our major cities and its caste system of regarding white as champion of development Dangarembga depicts so well when the real break at employment Tammbudzai gets by having to humiliatingly submit to her former white classmate for employment. This mournable body in the state of our personal and public affairs is what is stunting and regressing Africa.