BLACK HELEN OF TROY

If true the casting of a Black woman, Lupita Nyong’o, by the director Christopher

I came to this book with preconceived ideas of reading something written in sparse and controlled emotional intensity, the usual things I adore about Damon Galgut writing style I first discovered in books like: In A Strange Room and Arctic Summer. Galgut has relinquished that control in this more exuberant and linguistically loose book that caricatures the gestalt of a South African white (Swart) family through the years and generations. Its structure reminded me of Virginia Woolf's novel, The Years, which, like The Promise, is also a brilliant commentary on sociopolitical mores of the given age.

Woolf is noted as the first english writer to abandon the pretence of factitious coherence of the stream of consciousness, followed by William Faulkner and then mastered by Toni Morrison. A similar thing is happening on The Promise whose four chapters are based on four funerals of the members of this boorish white family over a span of forty years or so.

The first two chapters of the book are typical Galgut masterly writing craftsmanship: profound psychological observations that are beautifully narrated in unique phrases. For instance, this is the Pretoria most will immediately recognize: A city of moustaches and uniforms, Boer statues and big cement plazas. [p.33] There’s a snory sound of bees, jacaranda blossoms pop absurdly underfoot. [p.57]

Many people have complained about the abrupt changing voice from first to second personal to distant third impersonal on the novel. I didn't really have too much problems with this, in fact I found it enchanting, although sometimes it felt vertiginous, as if you were watching a movie captured on a fast shifting lense. I did feel the trick a little exaggerated when done mid sentence though, because it became too demanding to me as the reader. I found myself often having to reread the sentences and passages, even the whole page sometimes because I had lost my reading moorings, getting confused and wondering if I had missed something. Somewhere it took me three rereads before I discovered a ghost had entered the narrative. I first blamed this on my concentration lapses until I realised the forcing of a reread is probably part of the author's intentions because I found plenty rewards in some of the rereads, when suddenly sentences took on a more deeper meaning now that I knew where things were going. In fact the first two chapters of the book read like an epic prose poem. There, for me, lies one the strength and the beauty of this novel.

For those interested in such things the known history, to me, of varying voices in the english novel goes back as far as Dickens masterpiece, Bleak House. Recently, Tsitsi Dangarembga, in This Mounable Body, employs the trick of unpopular (in academic circles) second voice personal, which was mastered by the Scottish Poet, Ron Butlin, marvelous novel of degeneration, The Sound of My Voice. The idea goes beyond mere stylistics as a way of exposing dissonance between the societal mores and the character's inner lifer, especially when contrasted with their external failings. What these books, including The Promise, have in common is the unremitting critique of the political/ cultural/ spiritual vacuousness of the Zeitgeist of the respective eras they interrogate. The style, especially the tone of second voice personal, involves, even implicates, the reader in what is being interrogated or critiqued. Both the reader and the narrator are made to feel vulnerable, taken out of their comfort zone.

Something about The Promise reminded me of Xenophon's mock-heroic tale, Anabasis, also told in rapid shifts from one visual representation to another, and from those to an anecdote, and from there again on to a description of character. Xenophon, in telling the tale of retreat home by a defeated Greek army, does so in admirable chilling honesty and recognition of its collective hypocrisy. As they creep through mountains of Anatolia and fjords, occupying foreign lands, he is aware that they've been reducing into a horde of parasites who are no longer able to distinguish whether they're victims or oppressors amidst constant ambushes from people whose land they invaded. This tale is reduced to one family in The Promise, told with similar precision and appealing glint of irony that is acutely alert to the tragedy and obstinance of collective self delusion in most nationalist psyches with occluded memories.

The cinematographic narrative principle of The Promise is visible also in Ovid's Metamorphosis where, where each line must be full of visual stimuli in continuous movement by rendering verbs in the present. Its finite verbs are forced into a precise tense in order to locate actions in the time at which they occur. Even when the verbs are in the past the vocative effects a sudden sense of immediacy. This makes everything to happen before our eyes; new events quickly follow on by abolishing distance and changing rhythm, not by the change of tense, but the person of the verb, moving from third to second person in introducing the person of whom is about to talk about by addressing them directly in the second person singular. All that is interwined with slowing actions of rarefaction and pause.

The Promise's target is obviously the white reader. As such, sometimes as a black reader, you find yourself yawning from fatigue of having heard the story of anxieties of 'whiteness' before; from J.M. Coetzee to Antjie Krog to Marlene Van Niekerk. These writers have, for decades now, been studying in a literary form forms of national sicknesses that grow out of the psyche of the white South African generalized mistrust, profound social/personal alienation, and a gnawing sense of shame and fear for racial retribution. The Promise is the post ninety-four upgrade of this genre. It effectively uses racial/gender/sexual orientation and other scalpels of our age to excise and exorcise our zeitgeist tumours with penetrating psychological insights. Even the intertexuality of The Promise is deliberately made to echo those that came before, like Krog's Jerusalem Gangers with roots that goes back to W.B. Yeats: Slumber, little soldiers, while the minotaur stamps by. Slouching towards Bethlehem in the Free State. [p.32]

I'm not a fan of the current fetish of not using apostrophes: punctuation, diacritical marks and all. But when done properly, like in The Promise, it works just fine. Another writer I first encountered it on was Sally Rooney. Somehow it gives the book intimacy of a diary form. The Asian American writer, Charles Yu, in his recent book, Interior China, takes it into another level by writing the novel in a script form, font and all. I felt these similarities also in The Promise.

The serious issue I had with the book is the erasure of black people's interior lives, especially Salome's family for whom The Promise of the house/land was made. It is supposed to be the fulcrum by which the whole story hinges. I would accept this if it was done only by the caricatured white family as ruse to carry the story forward. But the author implicitly does it also in describing without explaining all his black characters. For me the driver, Lexington, is the epitome of this erasure. Though I dare not presume to impose themes on a writer's work I feel the opportunity to engage and critique the situation from the black point of view was lost in these instances.

In some interviews Galgut has explained this by saying his intent was to depict the black characters only in a way they appear from South African white Weltanschauung he was caricaturing. I wouldn't have a problem with this had he at the same time somehow succeeded in giving us a less stereotypical inner lives of the black characters also. Or to at least show us how things appear from their own interior point of view. Instead we only see them through cowered dialogue at best, and interior prejudice monologue of white others at worst. This surreptitiously gives an insulting idea that black people are not self reflective; they experience life like children only as an experience or a feeling. Even the last born family daughter (Amor) who is mostly depicted as having divergent views to the racialised boorishness of her family seems to sympathise with Salome only as form of rebellion and protest against her family prejudices. As the results she treats Salome as some kind of a project to settle scores through with her family. In short, she's OTHERING her even if from a point of no malice.

I can almost understand white writers for fearing being accused of cultural appropriation in this sometimes overly sensitive social media age with its accompanying Cancel Culture. But writers, especially fiction ones, must refuse to self centre by cowering to unjustifiable fads. Writers must not limit themselves from writing freely about issues they've no personal experience of if they've invested enough research and empathic imagination to it. Otherwise they castrate the magical wand of the imagination most of us go to fiction for. The important thing, when writing about characters you've no natural experience or affiliation of, is doing so with a sense of empathy, even deeper sympathy if they belong to the historically abused class/race/gender and other minority groups the white male hegemonic prejudices had tended to relegate them to in the past. What's irritating is when you stereotype characters, or write to reinforce the presumed insignificance of their lives or point view by silently religating them to the peripheris while using them as ciphers to advance your storyline. I've talked at length about this on my review of Marguerite Poland's A Sin of Omission that can be read down below on this site.

I am always baffled by white South African author's failure to write authentically about black South African lives; from Brink to Coetzee to Poland and now Galgut. Gordimer is probably the only white South African major writer who was able to write authentically about black lives by somehow portraying their lives in manner that goes beyond just serving the story plot or white literary gaze. I supposed we can say Gordimer somehow managed to ‘think black’ – i.e. to grasp imaginatively as well as intellectually the essence of the black historical experience, which requires a painful rethinking of basic assumptions by a white person.

You may say this door swings both ways, that black South African writers also are not know for delineating fully bodied and rounded white characters. I accept that critique. It is indeed a sin of our national omission as nation of non integrated racial people. It is glaring in our literature. But there's hope when you read Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu's two books, The Theory of Flight and The Theory of Man.

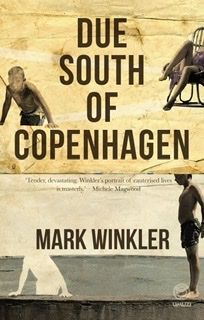

My favourite character in The Promise is Anton, the conscripted soldier who killed a black woman in the township. I found him more honest and believable in his anguish than his holier than thou younger sister Amor. In fact I even found the naively confused and opportunistically adept character of Astrid more endearing. I felt something for her because I recognised her greedy character of getting by at all costs. But I like Anton more because I welcome also,the emerging writing topics by white South African writers who are begining to wrestle honestly with their apartheid demons. It is also interrogated at length in Mark Winkler's Due South of Copenhagen. It's high-time we set aside the fictitious Rainbow narrative askde by dealing with our respective past with brutal honesty, especially where we were active, or implicated by our silent complicity. All these contributed into the psyche that makes for the mess which has become our wonderful nation in the Southern tip of Africa.

You can read The Promise, especially the story of Salome, on a metaphorical national level as deferred hope for the majority black South Africans whose frustration are starting to implode. This is rendered not only in the endemic violence of our society, but in the insurrection that led to commodity looting we had a taste of last July as our fire next time moment or Mzantsi Spring. The new generation, represented on the book by the angry son of Salome, is loosing patience with the gross lack of economic justice in our country. To his credit Galgut doesn't push the metaphor too far but only gives subliminal hints.

I loved The Promise though I felt something snapped on it from chapter three. In my opinion the characterization began to falter and the plot took a strange contrived angle [the kidnapping on the mall and subsequent murder felt tactless]. From there the whole story, for me, becomes silly and strains belief. Towards the end it had a touch too much of overtly parody, like a failed tragic comedy. They're a little disingenous those who try to excuse this on sweeping assumption that it is just a satire. It seems as though Galgut doesn't consider it as being just that, if anything he sees it as a caricatured social commentary of our past and present. Hence I felt it such a pity that this wonderful book deflated and felt rushed towards the end where it lacks, well, the quintessential Galgut masterly narrative refinement. Be that as it may, it is still a wonderful book of genuine literary stylistic innovation.