Don't Upset ooMalume: A Guide to Stepping Up Your Xhosa Game

Nqandeka writes with an easy familiarity of the Xhosa cultural background showing how the ordinary

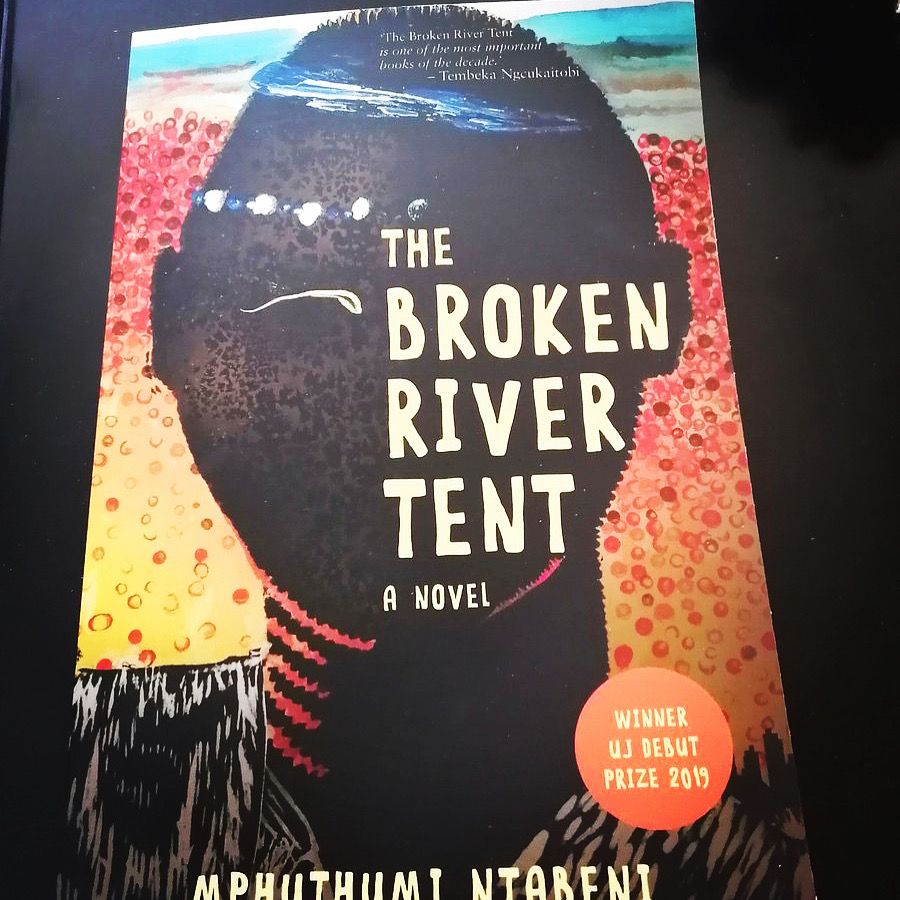

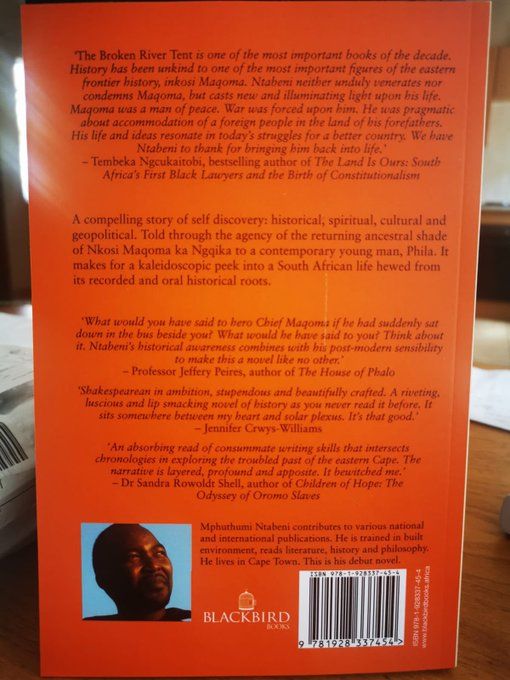

If you're looking for something to read this heritage month you probably should pick up The Broken River Tent. It reminds us how we got here from the Cape Colony Frontier history of 18th and 19th century Frontier. It is also extremely opinionated about our current situation.

When asked to read from The Broken River Tent (TBRT) I often select this passage I regard as the thesis of the novel:

The landscapes retain the memory of the departed. Beside your blood it is what you have in common with ages that came before you. The landscapes retain the ghost of the disposed and silently sing out their grief. This is why in the sigh of the sea you taste the breath of ghosts. And the mountains are like unmarked graves. Do not be afraid to take plunge on the depth of the abyss, because sooner or later you shall emerge on the side where you meet anew the stranger that is yourself …

TBRT answers also the challenge of James Baldwin who was of the opinion that the responsibility of a writer is to excavate the experience of the people who produced him. One of the crucial element in the human psyche is the need for belonging, to have a story, a historical narrative that defines and places you in space and time. Not only as an individual, but as a community, complete with mores, legends and myths.

African writers of historical fiction are currently in a process of redefining their identity by reinterpreting the facts of their past, telling them in the voices of Africans who, for a long time, haven’t been part of the telling (in written form) of their own history. The African history, most of the time, was written from a point of prejudice by those who socioeconomically and politically lorded over the African continent during the inglorious colonial era. Toni Morrison says this “…exercise is also critical for any person who is black, or who belongs to any marginalised category, for, historically, we were seldom invited to participate in the discourse even when we were its topic.” She speaks about reaping open the veil of terrible deeds and things that were done and said about us as black people. Hence memory weighs heavily in what we write.

As black people this memory weighs not only on stories we grew up with as legends and myths, but we feel the heaviness of it in our genes and ancestral lands we were dispossessed of. Zora Neale Hurston puts it this way: “Like the dead-seeming cold rocks, I have memories within that came out of the material that went to make me.” The historical novel, then, is collection and colloration of things that made us. These “memories within” are the sub soil of our work. Because historical facts, memories and recollections do not give us total access to the unwritten interior life of our people in the past we lean also on the imagination, informed imagination. Only the act of an informed imagination can give the psychological insight into historical facts.

Historical fiction is what Morison calls the Literary Archeology:

On the basis of some information and a little bit of guess work you journey to a site to see what remains were left behind and to reconstruct the world that these remains imply. What makes it fiction is the nature of the imaginative act: my reliance on the image on the remains in addition to recollection, to yield up a kind of a truth…

During interviews I often get asked the question about whether historical fiction is fantasy, myth, magical realism, biographical or romance? My answer is: It is some and none of that. It transcends all these labels. The single gravest responsibility of a historical novelist is not to lie. Toni Morrison again. She says: When I hear someone say, “Truth is stranger than fiction” I think that old chestnut is truer than we know, because it doesn’t say that truth is truer than fiction; just that it’s stranger, meaning that it’s odd. It may be excessive, it maybe more interesting, but the important thing is that it’s random and fiction is not random.

According to Morrison the crucial distinction is not the difference between fact and fiction, but the distinction between fact and truth. Because facts can exist without human intelligence, but truth cannot. Just because people didn’t write their history or their interior reactions to the happenings of history doesn’t mean they didn’t/don’t have them. The question is how, as writers are we now going to access those interior lives. This is the gap the historical novel seeks to bridge. As people who’ve been lied to and vandalised to prop up other civilisation by our sweat and blood our real authentic access to our history is our bodies, the blood that runs through them, the genetic and oral memories told in our being alive into the zeitgeist we were born into and the land of our ancestors. Like Maqoma in TBRT we refuse to comprise ourselves on this issue even if that is purchased by our deaths.

Authors arrive at text and subtext in thousands of ways, but no matter how “fictional” the account of our writers, or how much it was a product of invention, our act of imagination is always bound up with memory. [Morrison] The Japanese art of origami teaches us that paper has perfect memory. No matter how many folds you make on it the paper remembers it all, because of its malleability. The folds, to the paper, are like scars of experience/history. According to Morrison water also has perfect memory. She says:

You know, they straightened out the Mississippi River in places, to make room for houses and liveable acreage. Occasionally the river floods these places. "Floods" is the word they use, but infact it is not flooding; it is remembering. Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was. Writers are like that: remembering where we were, what valley we ran through, what the banks were like, the light that was there and the route back to our original place. It is emotional memory what the nerves and the skin remember as well as how it appeared. And a rush of imagination is our "flooding." Along with personal recollection, the matrix of the work I do is the wish to extend, fill in and complement slave autobiographical narratives. But only the matrix. What comes of all that is dictated by other concerns, not least among them the novel's own integrity. Still, like water, I remember where I was before I was "straightened out."

A historical novel then is much more than just an artistic impression of history, or reinterpretation of history. It is an act of re-remembering the rock we were hewn from, an ancient path before we were straightened out. It is a process of building a coherent narrative of the past. Of finding out how all that relates to the present, because how we deal with the past informs our identity. I venture to say that the historical novel is a necessary scaffold to national consciousness, and a crucial part of the mystical strife towards universal humanism that transcends the fracturing effect of factional past. This is why historical novels are crucial, especially for nations that are still seeking their national identies, rather who want to reinteprete into an authentic path that is integrated to the traditions, cultures, customs and moores of its people.

The strength of a historical novel is in exploring psychological and emotional terrain of history. Historical novelists do not seek to compete with historians. Like bees they suckle at the pollen from the flowers historians plant to weave from it palatable combs of honey for the ease of public consumption. They interrogate gaps and unhealthy silences of history; confront sometimes even the bias interpretation of facts by rented historians. They put flesh and blood by breathing into the dry bones of history, to give mobility to the static facts of history. They provide a way of thinking about society as a place where history is still unfolding, where individuals can still play a role in shaping it. When historical fiction is done well it doesn’t betray history but opens it up for inspection.

The aim of hstoricl novels should be to put readers in the vitality of historical moments and places in time. Common to architecture the historical novel has the ability to mine the genius of the landscape/place into becoming a metaphor for the geometry of sustainable habitation for us in this little environmental space our bodies have adapted to called the earth. Hence I gave my protagonist, Phila, an architectural profession.

As a way of introducing people to TBRT I often read this passage at the beginning of the book, when Phila learns of his own father’s death. He feels the weight of wasted time being distant to his father until they ran out of time. Running out of time, the river collapsing to the vast sea—deep calling unto deep—is essentially what death is:

Rivers are instructive and fascinating. In a river stream there are levels of flow. Where inhibitions occur swirls develop. A swirl creates noise but does not run deep. If it tries to take short-cuts it often eddies, spins off and dies. This is due to lack of depth. Or else it scatters into a swamp that festers with either life or disease. If the eddy is lucky, it gets caught up again in the deeper current of the river to become part of the wider, silent stream.

No stream runs higher than its source.

Parents are natural banks and channels for the run of their children. Without banks, the water becomes a swamp that breeds infectious diseases. Channels that are too deep become choking dungeons where children can’t breathe, or can’t take a better view of the world. Channels of proper depth and right direction carry their children as tributaries to the fertile depths of the ocean, where life gestates life, and deep calls unto deep!