Don't Upset ooMalume: A Guide to Stepping Up Your Xhosa Game

Nqandeka writes with an easy familiarity of the Xhosa cultural background showing how the ordinary

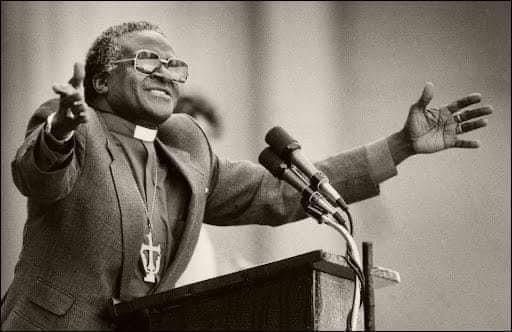

The death of archbishop emeritus of the Anglican church, the right reverend Desmond Mpilo Tutu, set in motion predictable emotions among the angry young political activists of the extreme left in South Africa. Archbishop Tutu is seen by the young radicals on the same growing light of disappointment about the older generation, like Mandela. They're accused of being sellouts by coping out into what is derogatory referred to as White Monopoly Capital (WMC). In general the WMC refers mostly to a few white families that controls most of the South African economy, like the Ruperts, the Oppenheimers and the rest.

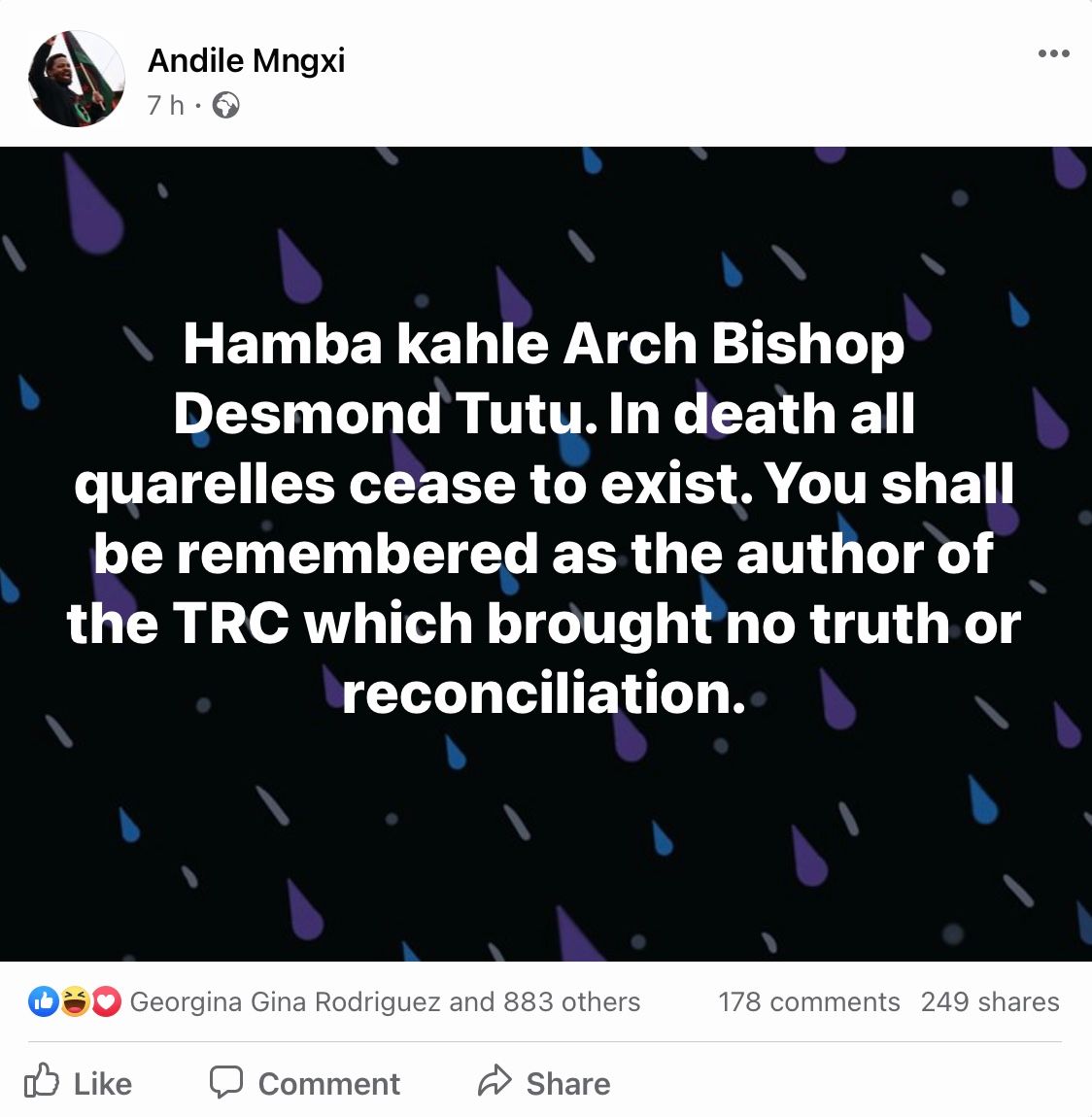

The South African radical left youth in particular believe that the WMC are the real economic policy controllers of the ANC government since the early nineties when they approached the organisation in exile. Thabo Mbeki, in particular, who acted more as a prime minister under the first South African democratic dispensation of the Mandela administration is seen by this youth as the one who orchestrated the sellout political freedom without economic justice. Archbishop Tutu is guilty because of his association with the Truth and Reconciliation Council he chaired. On the news of the arch's death one of these you g left radicals wrote on his FB wall: Go well Arch Bishop Desmond Tutu. In death all quarelles [sic] cease to exist. You shall be remembered as the author of the TRC which brought no truth or reconciliation.

It would have been more ironic had the Arch died on the 16th December, which is South Africa's public holiday known as the Day of Reconciliation that used to be called Digaan's Day. Dingane, spelled Digaan by white settlers of the epoch (born c. 1795—died 1840) was a Zulu king (1828–40) who assumed power after taking part in the murder of his half brother Shaka in 1828. After 1836 Dingane was faced with invasions of white British and Boer settlers into Natal, to the south of the Zulu kingdom. Dingane, wanting to be done with white settlers once and for all, summoned their leaders on pretence of a peace treaty and killed all six of them on his royal kraal in uMgungudlovu. What happened on that fateful morning of 6 February 1838 when these Voortrekker leaders, including Piet Retief and his companions were overwhelmed and killed by the Zulu stronghold has no clear written record since all the Voortrekkers who were killed.

No white people eyewitness of the account exists of the massacre. Francis Owen, a British missionary based at Mgungundlovu, is said to have watched from a distance of safety of his mission station as events unfolded. Later on he wrote about it in his diary. A second non-Zulu eyewitness of the massacre was a twelve-year-old boy, William Wood. He was the son of a British trader who lived with Owen and his family. Wood understood Zulu well and often acted as interpreter for Dingane. It is unclear exactly where he was when the incident took place. His report was published in Cape Town two years after the event but where, when and how he recorded it on paper is still unknown. A third non-Zulu eyewitness was Jane Williams, who was later known by her married name, Jane Bird. She was a Welsh girl who worked as servant for the Owen family. She also viewed the events from the mission station. Her report was published in the Orange Free State Monthly Magazine in December 1877. It is not known when she wrote it. For Afrikaners, 16 December was/is commemorated as the Day of the Vow, known as Day of the Covenant or Dingaansdag (Dingaan's Day). The Day of the Vow was/is their religious holiday commemorating the Voortrekker victory over the Zulus at the Battle of Blood River in 1838, and is still celebrated by some Afrikaners.

The period between the 16th to Boxing Day is usually fraught with pent-up political emotional baggage in South Africa, which is why I found it amusing that the Arch, in his perennial humour, chose to make his final departure during these dates, which naturally facilitated the strong discussion about the faltering of the so called Rainbow Nation, a term he also coined prematurely perhaps. It would seem then, even in death, the controversy and vague strife of failing South African reconciliation project has followed the arch bishop to the grave since the days of the TRC.

I feel it unfair to apportion the blame of the TRC demise on him though, after all he was just its commissioner and chair, appointed by the government administration of Mandela. Also, the TRC report and some of its recommendations were sensible, including the suggestion for some form of taxations for WMC that benefited most from the apartheid era. Most people of the South Africans feels that, at least, the WMC should have been made to pay for SA's apartheid debt to the Brentwood institutions; and also compelled to do national programs of skill training for our black youth in particular. Such things were on the TRC recommendations. The ANC government, under the administration of Thabo Mbeki, rejected those recommendations. Instead it gave the WMC free ticket to move their moolah to occidental golden nests like the London stock exchanges without ever contributing a cent to national reconciliation of the country. So, perhaps instead of going for low hanging fruits the radical youth of the left should be demanding more answers from the ANC who should bare the greater brunt of the failure and impotence of the TRC. The former president, Thabo Mbeki, in particular has a greater case to answer on this case than the saintly archbishop.