BLACK HELEN OF TROY

If true the casting of a Black woman, Lupita Nyong’o, by the director Christopher

Tengo Max Jabavu belonged to a generation born at the narrowing edge of South African possibility. He came of age at a moment when African intellectual life was still animated by faith in education, professional achievement, and moral leadership, yet already shadowed by the tightening architecture of apartheid. His life—promising, disciplined, and tragically brief—was shaped by inheritance and restraint, and by an aspiration at once modest and radical for its time: to become a doctor, when such a calling signified not merely a profession but a vocation of service under conditions of systematic denial.

He was born into one of South Africa’s most distinguished African intellectual families. His father, Professor Davidson Don Tengo Jabavu, was a towering figure of the Cape liberal tradition—educator, editor, public intellectual—who believed, with the late nineteenth-century conviction that never quite abandoned him, that education and moral suasion could yet carve a space for African dignity within a hostile colonial order. He was one of the founders of the All African Convention (AAC), which sought to unite all non-European opposition to the segregationist measure of the South African government.

Tengo’s mother, formidable in quieter ways, anchored the household in discipline and moral seriousness. Tengo was the only son, the younger brother of two sisters whose lives would unfold cosmopolitically—one in Uganda, the other in Britain. One of them, Noni Jabavu, would later become a major literary voice. Together, the sisters would ensure that his death was not merely a private loss, but a public wound rendered into language.

In the Jabavu household, excellence was not optional. Education was not preparation for life; it was life. The children grew up conscious that they carried a name already inscribed in South Africa’s intellectual history. Their grandfather, John Tengo Jabavu, had founded Imvo Zabantsundu, the first newspaper written by and for Africans as a platform that helped articulate some of the earliest arguments for African intellectual equality and participation in global modernity. To be a Jabavu was to inherit not privilege, but responsibility.

Fort Hare and the Inheritance of Hope

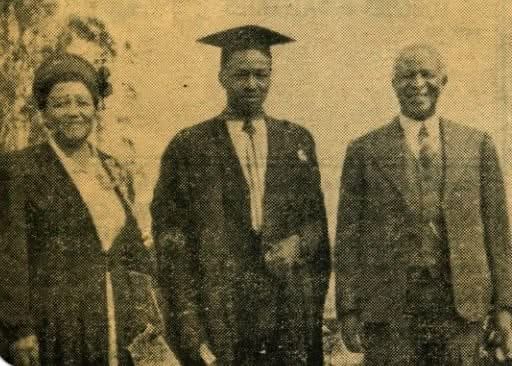

Tengo’s intellectual formation followed a path familiar to the Black elite of his era. At the University of Fort Hare, he completed a BSc in Chemistry in 1950, joining a remarkable cohort of African students who still regarded the institution as a site of disciplined hope rather than impending betrayal. This was the Fort Hare that had produced lawyers, teachers, clergy, scientists—men and women who believed, with quiet seriousness, that professionalism itself could be a form of resistance.

Chemistry was not an obvious choice for a young man raised among politics and letters, but it revealed something essential about his temperament. He was methodical, inward, quietly ambitious. He did not seek attention. Those who knew him recalled a man of reserve rather than flourish, more inclined to diligence than rhetoric—a disposition ill-suited to spectacle but well matched to medicine.

From Fort Hare, he proceeded to the University of the Witwatersrand, where he undertook medical studies. Wits, liberal in reputation, was already constricted in practice, uneasily situated within a state that was sliding toward authoritarian racial rule. Yet for Jabavu, medicine represented both scientific mastery and ethical purpose. To qualify as a doctor was to enter a profession apartheid sought to ration and restrict, and to claim, by merit, a place it preferred to deny. As he neared qualification, his letters home were filled with plans—travel, work, return—written with the calm assurance of someone who assumed the future would meet him halfway.

A Cosmopolitan Family, a Shattered Axis

While Tengo studied in Johannesburg, his sisters lived abroad—one in Uganda, the other in London. The Jabavu family had become quietly diasporic, stretched across Africa and Europe, yet held together by letters, expectation, and affection. Tengo was the axis around which their hopes revolved: the son who would become a doctor, the brother who would travel, the man who would return equipped to serve a people increasingly under siege.

It is this sense of expectation, abruptly severed, that animates the opening of Noni Jabavu’s Drawn in Colour, her first and most influential autobiographical work. She begins poignantly with catastrophe:

The cable arrived for me in London from South Africa. It was from my father, about my only brother, Tengo, twenty-six years old, reading medicine at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. The week before, I had had a letter from him outlining plans he was making for when he would qualify in a few months’ time. My sister and I hoped he would take a holiday abroad after the long years of training, stay with her in Uganda, East Africa, where she had married and gone to live, then come on to stay with me in London where I had married and lived. He would thus see both countries of his sisters’ adoption. He was the youngest of the three of us, the only son, and it was some time since we had all seen one another.

But on March 8th, a young messenger boy whistled up to my house, stamped jauntily on the steps and rubbing his fingers to keep warm while waiting for a possible answer to the message he delivered:

‘TEGO SHOT DEAD BY GANGSTERS FUNERAL SUNDAY 13th JABAVU’

The message, sent in haste from Cape Town, was wrong in its details and brutal in its compression. Tengo was not killed by gangsters. He was shot and killed in a tragic accident by a friend, in Johannesburg, just months before completing his medical degree.

He was twenty-six years old.

The circumstances were mundane, senseless, and therefore unbearable. No political martyrdom could redeem the loss. No grand narrative could rescue it from absurdity. It was simply a life stopped.

Grief Across Continents

For his sisters, the journey home was also a reckoning. Flying south from London, one of them saw Africa unfold beneath her for the first time in its immensity. What had once been inheritance and abstraction became physical fact—vast, exposed, overwhelming. Grief sharpened perception. The continent appeared not as promise, but as distance: the distance grief had travelled to reach her. Writing became the means by which that distance could be crossed, measured, and survived.

Through Noni Jabavu’s prose, Tengo is preserved not as a flesh and blood brother and a diligent, hopeful, unfinished life. His death becomes emblem and heroic struggle for a black life and the quieter tragedies that crowd South African history about black lives that were prepared for service, and extinguished without warning. His is remembered because someone close to him possessed the language to remember it. Numerous other went to the dark with hardly a scream.

The Meaning of an Interrupted Life

Tengo Jabavu did not live long enough to become a public figure. He left no speeches, no medical practice, no institutional legacy. Yet his life carries historical weight precisely because it was so typical of its promise, and so devastating in its end.

He represented a generation educated for a country that was closing its doors even as they approached them—a generation raised to believe that discipline, intellect, and professional excellence could secure a future, only to discover that contingency, violence, and structural cruelty often arrived first.

In his death, the Jabavu family lost its only son. South Africa lost a doctor it desperately needed. History lost one of its innumerable almosts—those men and women whose contributions were foreclosed not by lack of talent, but by the randomness and brutality of life under a colonial order hardening into apartheid.

Tengo Jabavu’s story endures because it reminds us that history is not only made by those who lived long enough to act, but also by those whose curtailed lives illuminate what was possible—and what was lost—in the time they inhabited.