BLACK HELEN OF TROY

If true the casting of a Black woman, Lupita Nyong’o, by the director Christopher

BELOW IS A SUMMARY OF AN EMAIL I RECEIVED FROM AN ACADEMIC I RESPECT. IT IS FOLLOWED BY MY FULL REPLY TO HER:

I was disappointed to hear you encourage students treat your book characters as real people. For generations, literature students have been told never to treat characters as if they were real people. Literary theory is replete with warnings against committing this cardinal sin.

We must always remind ourselves that characters “exist only as words on a printed page,” and therefore “have no consciousness.” Should the “feeling that they are living people” arise, we must resolutely repress it, for it is an “illusion.”

We must remember that if characters fascinate us, it is only because they “invite cathexis with ontological difference." We must never violate academic protocol by crossing the boundaries between literature and life.

We must never forget that “le personnage … n’est personne,” that the person on the page is nobody.

__________________________

Your email transported me to 1920s and 30s discussions whose argument I wrongly thought were exhausted then, between the modernist and post modernist. Anyway, as someone who has no dog on the fight perhaps it is good to engage on the topic with a proviso that: I am not into to either modernism or what is referred to as postmodernist literature. I am against making such values the hidden and unchallenged foundation of literature, for then we will fall into the trap of projecting the values of formalism onto every kind of literature. I think writers should be given a clean slate to create form according to their wishes or inspiration. What I don't understand from your question is why you think writers should in turn pontificate about how readers must react to their works. Once the book is published, in my opinion, it is on public domain, and in a way, outside the writer's control.

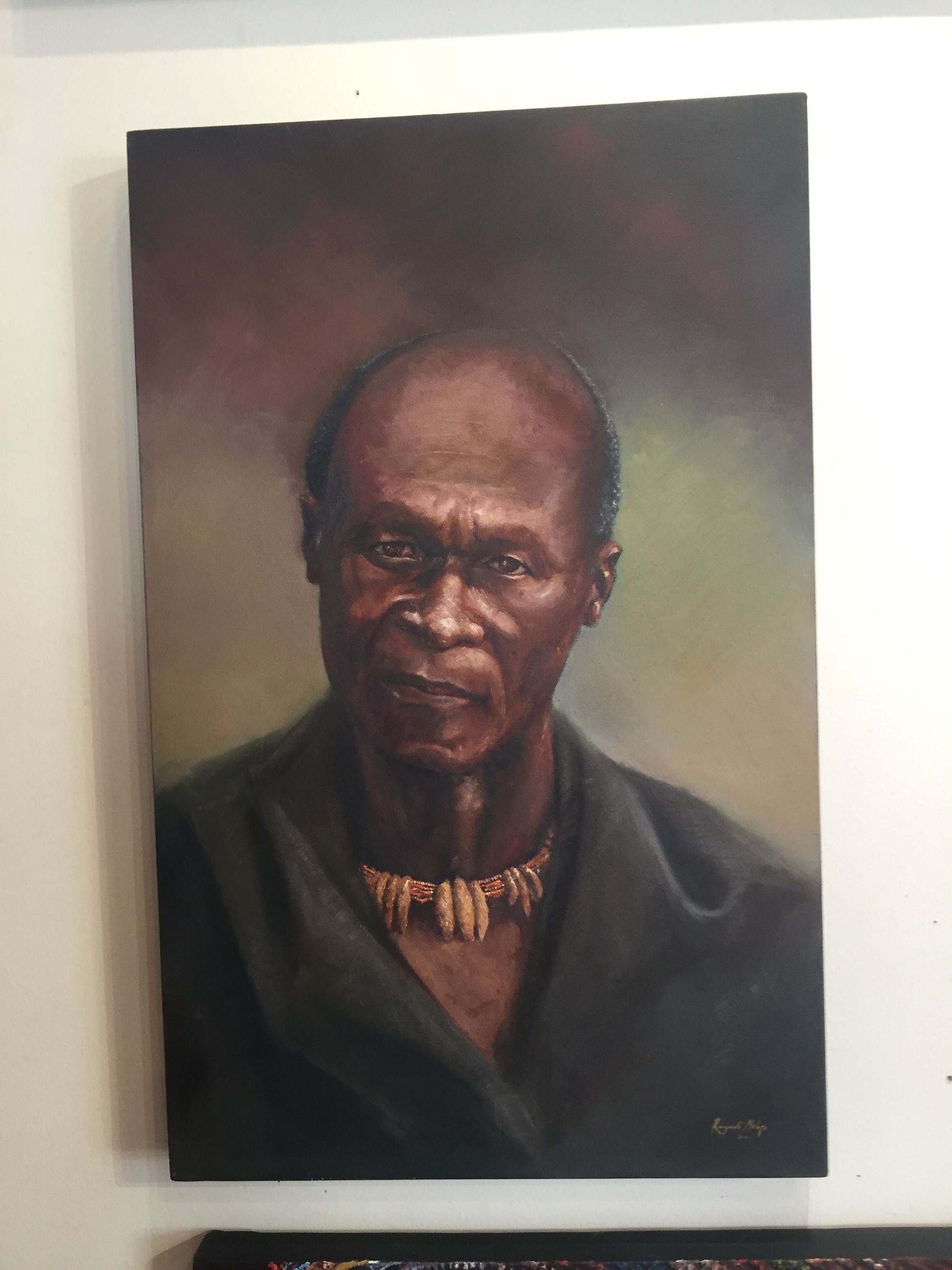

You intimate that readers should not be encouraged to react towards characters as though they were ontological, that is real in a physical and conscious sense. Does that extend to past historical persons who are transmitted to us, by necessity, as characters by historical narrative? What is historical narrative if not the impressions historical facts and projections have made on someone who has investigated them? Why must this narrative be treated as being tangible as compared to imagined facts? Surely the drive behind the imagination in narration is the same as one behind historical actions. Why then are imagined experiences discounted by academic literary criticism and not the narrated 'real' ones? Remember that historical reality is real only to those who experienced it, the rest of us experience it only through narrative and characterisation, the same way we experience stories on novels. We must take it on faith from those who narrate them to us. Of course, with historical facts you can make comparison with recorded facts. But my point is that, even recorded facts are not captured live, they're impressions of those who were present, or who have studied the incidences. This is why you sometimes find people today who disputes some historical narratives based on the fact that not enough historical collaborations exist to prove beyond reasonable doubt that those people existed, like Abraham. So are we to belittle those who associate with Abrahamic faith based on the fact that his existence is a doubtful historical fact, thus never ontological? Do the faithful care?

Secondly, are you disputing the fact that our familiarity with characters, whether ontological or not, renders them very emotionally potent to us, which is the reason why the readers sometimes associate with them for real? Psychologists have for years been interested in what they call "experience-taking". This is the process of consciously or subconsciously taking on the traits, attitudes and behaviours of literary characters from books, theatre or movies. Our favourite characters, ontological or not, are often such because we strongly identify with them. And the root of our attraction to them may not be that we want to be like them, just that we really enjoy spending time with them.

Thirdly, readers are not as naive as you suppose them to be. Even in our current age, where autofiction is popular, readers are able to distinguish between the writer's alter ego and their lives. They know that writers, consciously or subconsciously, often insert elements of their own personality into characters. So, in a way, we can say readers who treat characters as real are seeking a relation with an ontological human, in this case, a writer who brought to life a character of their own imagination also. Who is it to say it is not based on real emotions or real experiences? Is this not the same association they're required to make with the histoeical character? This maybe why readers love interacting with writers more than they do reading literary criticism. Maybe the ultimate mark of a truly memorable fictional character should be how often we take them with us when we head back to reality.

Lastly, you talk about your "…permanent disdain for popular fiction for appealing to base human emotion while eroding genuine moral values and quality of literature." Thanks for excluding my book from the list, but I still find your statement problematic. I am the first to admit to holding certain moral values I try to live my life by. And I do my best to uphold certain literary standards (especially of classical literature), because it is what appeals to me. But far from me to think mine should be a universal standard of moral and literary aptitude. When challenged to substantiate my beliefs and ideals I do so. But if someone chooses different from my standards I accept that, as long as they don't impose theirs on me also. I find better values and enjoyment in reading Homer or Mqhayi, but I am fine with those who find it on E.L. James's Fifty Shades of Grey. Secretly, of course, I habour thoughts that they're debasing their natural sexual instinct, just as much as I know they think me a tad snobbish.

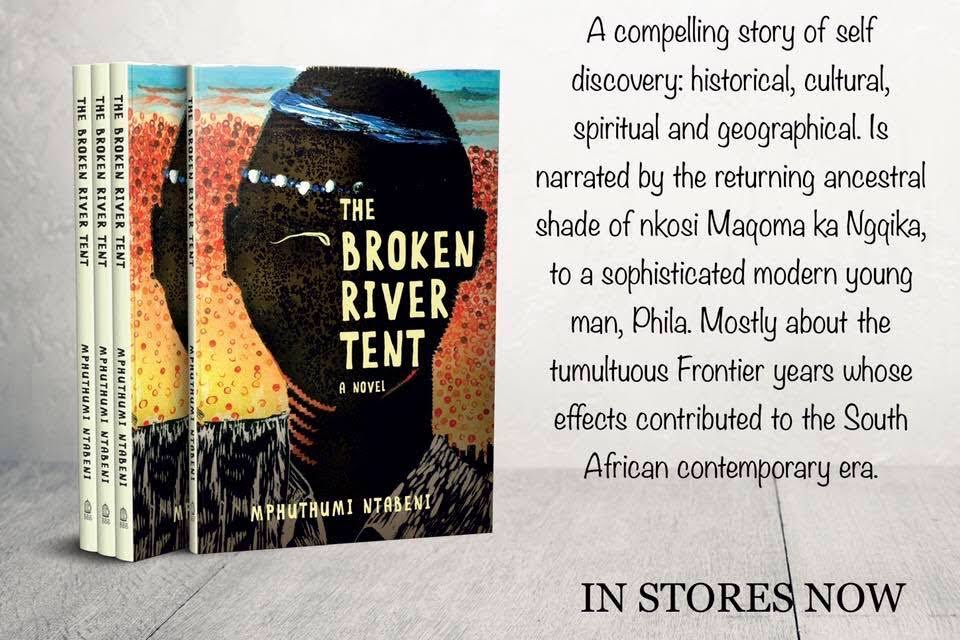

I honestly think you can maintain your standards without necessarily becoming highbrow about them, or heap scorn on the popular or middlebrow culture. The philosopher, Tamar Gendler, says we have two competing levels of consciousness — belief and alief. The former being what governs our intellectual knowledge that yes, fiction is not fact. Whereas the latter what she calls “alief”, is our brain’s ability to suspend our belief that fiction is not “real” — which is what makes consuming literature enjoyable. I see nothing wrong with a reader having an emotional identification with a character, as long as they know where they're in any given time. In fact, if I may, this is the threat my character Phila felt in The Broken River Tent, that of not knowing whether he's still reading books or facing reality in seeing the historical character of Maqoma. His beleif and alief somehow got mixed up and is what unsettled him through out the book.

Thank you for the engament. I must confess, I nearly didn't take you seriously because I thought you were just baiting me.

Have a great weekend

Mpush