BLACK HELEN OF TROY

If true the casting of a Black woman, Lupita Nyong’o, by the director Christopher

Whenever I arrive on a new place I look forward to discovering it with my feet. This is why I was rather disappointed when it rained the whole week of our arrival for the JIAS (Johannesburg Institute of Advanced Studies) Fellowship 2021, which is ran by the University of Johahannesburg. I'm no stranger to Johannesburg's swallowing streets, having spent my early tertiary years studying at Wits University during the later part of our turbulent eighties. As a flaneur I feel the only way to really show up in place, especially cities, is by memorising it with your feet. So the moment the sun was up I was on the gad.

Towards the CBD Johannesburg is not really a walkable city, it is mostly a wasteland of billboards and other intrusive noises and transgressive behaviours. Architecturally, with uninspiring stone-and-steel-and glass, is somehow something of an eyesore also. But even this part of Goli, the golden city, acquires a certain grandeur when its wet deserted streets refuse to succumb to the forced paralysis of rain and pandemic lockdowns.

Those who know Melville will know that a view from its numerous koppies give pay to the fact that Johannesburg is the city with the biggest man made forest on earth. Its numerous koppies spits you out into different different directions of the city. I chose the one that smuggles you into Sophaitown during my first walk. I was glad to see the old spirit of Sophaitown slowly slipping back after the long years of apartheid Triomf. For few minutes I walked behind an old white lady on tripod walking frame with whom I was dying to strike a conversation about how she must feel now that her neighbourhood has become black and brown again. She didn't seem like someone who entertain such talks so I passed her by to concern myself with my own thoughts.

There're myriad reasons why one applies for a writting fellowship, I just can't pinpoint exactly which one made me apply to the JIAS. One of these wll do just well anyway:

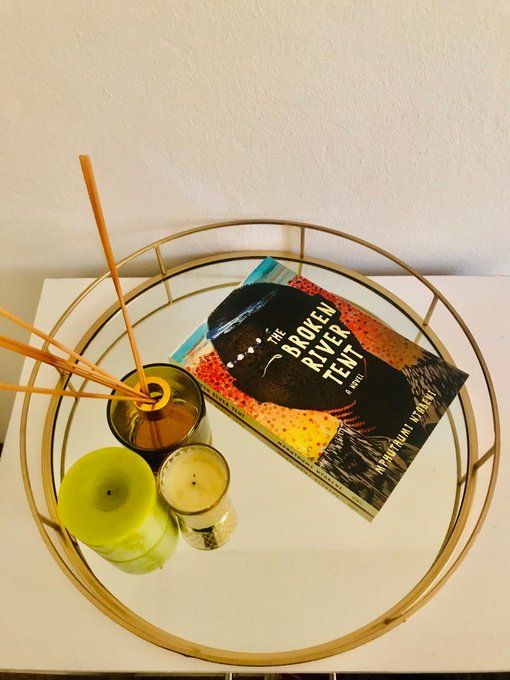

1. To write the second instalment of my planned trilogy, The River People (about the impact of colonialism in the history of amaXhosa), which The Broken River Tent was the first instalment.

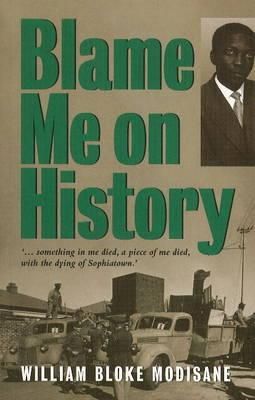

2. To finalise the research and write the literary biography of Bloke Modisane who, with a taste of bile in his mouth wrote in Blame Me On History:

Something in me died, a piece of me died, with the dying of Sophiatown; it was in the winter of 1958, the sky was a cold blue veil which had been immersed in a bleaching solution and then spread out against a concave, the blue filtering through, and tinted by, a powder screen of grey; the sun, like the moon of the day, gave off more light than heat, mocking me with its promise of warmth--a fixture against the grey blue sky--a mirror deflecting heat and concentrating upon me in my Sophiatown only a reflection.

It was Monday Morning, the first working da away from work; exactly seven days ago I had resigned my job as a working journalist on Golden City Post, the Johannesburg weekly tabloid for the locations. I was a free man, but the salt of bitterness was still in my mouth; the quarrel with Hank Margolies, the assistant editor, the whiteman-boss confrontation, the letter of resignation, these things became interposed with the horror of the destruction of Sophiatown. I was a stranger walking the streets of blitzed Sophiatown, and although the Western Areas removal scheme had been a reality dating back to some two years I had not become fully conscious of it ...

So, walking these streets, I shared something of a rising bile to the mouth with Bloke.

3. Because my mother died last September, making things lose their colour in my eyes, thus exacerbating an element of weltschmerz, world weariness, within, making me desperate for the timeout from the general nature of things. Anyway, the important thing is that I am here at the JIAS now, and plan to accomplish one or all of these things.

It felt pertinent to be thinking about Bloke while walking the streets of Sophiatown he once traversed. To him these were streets and fields of proscriptions and defiances he narrates so well in his autobiographical bildungsroman, titled: Blame Me On History. I can imagine him 'skulk around the arcades' the apartheid regime bulldozed to dust. He interpreted the faces he met as people who came to the city seeking freedom, economic, psychological, sexual and otherwise. As I pass the corner robot, where a group of young Zimbabweans, with different tools of their respect trades, wait for bakkies to pick them up for hire, my mind races to the parable of Yeshua, the Christ to us Christians, made about the vineyard master who paid the late coming workers the same wage as those hired in the morning. When the early workers grumbled he reprimanded them for questioning his generosity. I wondered if preachers instead of preaching the Bushiri-like rubbish of the so called prosperity Gospel ever think to apply this parable against the xenophobic feelings of South Africans.

I doubled over and continued back towards Westdene Dam still plunged in my reveries and curiosities, attuned to the chords vibrating on the city streets, glimpsing its unofficial history through the inspired graffiti of modern prophets, according to Paul Simon.

I think to myself: People who don't do walks will never know the total freedom that's unleashed by the act of putting one foot in front of the other without any real intentions of getting anywhere. Or really understands what happens when nothing is happening. Nor the serendipity that comes from encountering things that change your life without your due deliberations.

I'm sure even that eponymous UJ cafe, owned by the Somali guy, himself seeking Bloke's freedom who sold me an expired airtime, has meaning in the ledger of haven where nothing occurs without an eternal echo.

They say you're not the walks right if you don't get lost at least once in a while. Jus as I was beginning to panic, somehow serendipitously, after descending a steep decline, I was before this familiar strange face brick building with caryatid columns and perched concreted cherubs playing flutes, harps and xylophones. Something about it feels like you're entering a fairytale.