BLACK HELEN OF TROY

If true the casting of a Black woman, Lupita Nyong’o, by the director Christopher

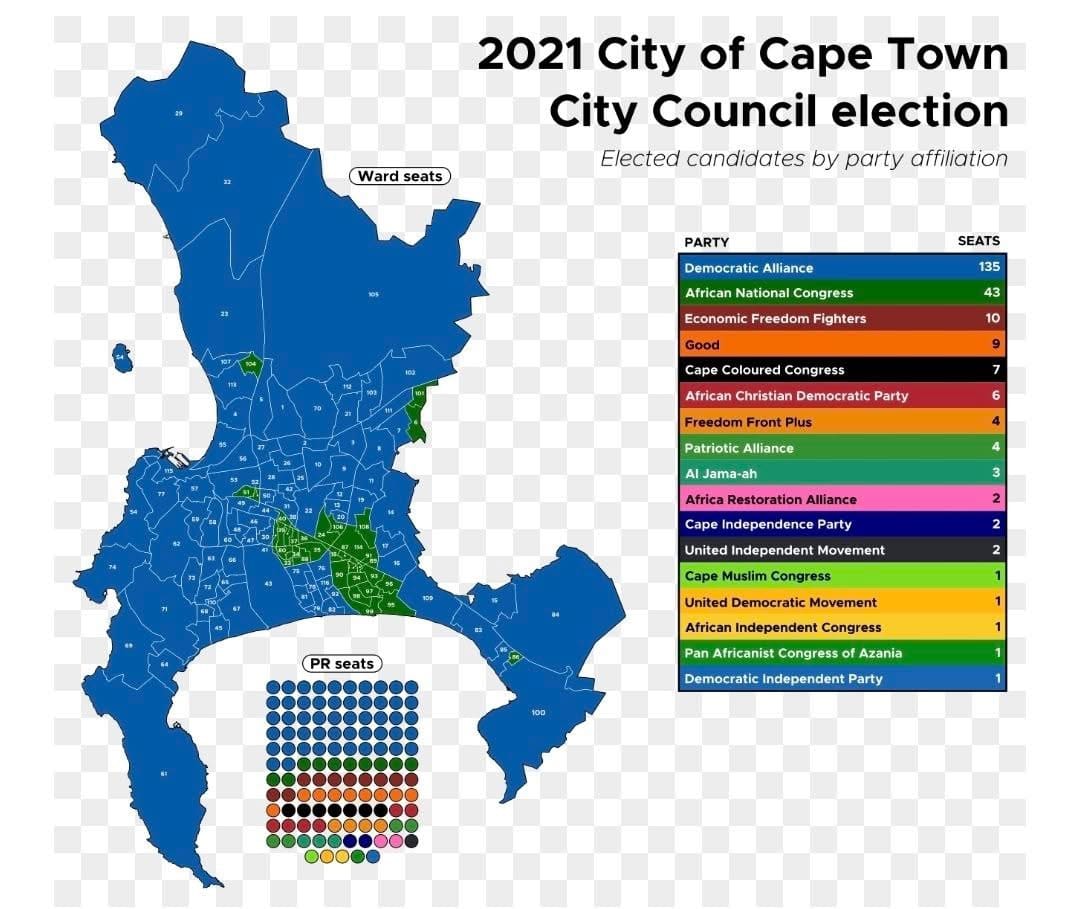

Cape Town’s Real Opposition Crisis Is Not in Council — It Is in the Voter Roll

As Cape Town moves toward the 2026 Local Government Elections, the city faces a paradox: a council filled with many political parties — but almost no real opposition. On paper, the composition looks pluralistic. On the ground, it delivers little challenge to the ruling party.

According to the latest council seating, out of 231 seats the ruling Democratic Alliance (DA) holds 134. African National Congress (ANC) follows with 43 seats; the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) has 10; GOOD 9; Community Constituency Coalition (CCC) 7; African Christian Democratic Party (ACDP) 6; Patriotic Alliance (PA) 5; Freedom Front Plus (VF Plus) 4; and the remainder share the remaining one or two seats each.

Yet despite this multi‑party mosaic, real competition is missing. The DA governs with the confidence of a party unchallenged over two decades — insulated, unaccountable, and increasingly detached from the daily struggles of many Capetonians. Services lag, tariffs rise, inequality deepens and for many residents — particularly in poor communities — life grows harder.

But the DA’s greatest strength may not be its political skill. It may be an even more pervasive and damaging phenomenon: non‑voting.

South Africa’s Local Government Election turnout has steadily fallen:

• 2006 — 48.4%

• 2011 — 57.6%

• 2016 — 57.0%

• 2021 — 45.9%

This decline mirrors Cape Town’s own collapsing participation, especially in township and marginalised wards.

When voters stay home, they don’t cancel their vote — they surrender it. They allow incumbents to govern unchecked. Non‑voting becomes endorsement by default. It sustains unsound governance.

To change Cape Town, opposition parties must shift from press‑conference politics to grassroots mobilisation, especially youth‑focused voter registration and ID‑application drives. Local Government determines who gets roads, housing, clinics, and investment — and every community that does not vote is ignored first.

Your vote is not symbolic — it is strategic. The future of Cape Town belongs to those who register, organise, and show up.

Voter Turnout Decline Chart (2006–2021)

Infrastructure Development Assessment: Cape Town

Infrastructure Development Assessment: Cape Town

Cape Town’s infrastructure investment patterns reveal a consistent imbalance: affluent suburbs receive more reliable, more rapid, and more prioritised infrastructure than townships and peripheral communities.

1. Roads & Transport:

• Wealthy areas receive frequent resurfacing, traffic management upgrades, and rapid pothole repairs.

• Townships face long delays, seasonal flooding, and limited pavement infrastructure.

• MyCiTi’s expansion into poor areas (Phase 2A) remains delayed, while affluent routes were prioritised.

2. Water & Sanitation:

• Affluent suburbs enjoy stable water pressure and fast responses.

• Township residents experience recurring sewage spills, blocked drains, and slow repairs.

3. Public Amenities:

• Parks, libraries, and sports facilities in rich areas see continuous upgrades.

• Township amenities face underfunding, staffing shortages, and inconsistent maintenance.

4. Housing & Spatial Development:

• Social housing is blocked near affluent areas and pushed to the outskirts.

• Development approvals favour high‑end projects.

Cape Town’s infrastructure patterns entrench a structural geography of privilege. This is why Local Government Elections matter: they determine whose neighbourhoods are prioritised and whose are neglected.