BLACK HELEN OF TROY

If true the casting of a Black woman, Lupita Nyong’o, by the director Christopher

If true the casting of a Black woman, Lupita Nyong’o, by the director Christopher Nolan in the film, The Odysseus, as Helen of Troy, is not about provoking novelty but returning the myth to its original terrain of symbol, contradiction, and human consequence.

Helen of Troy is not a historical figure in the modern sense. She is, as Homer gives her to us, “a wonder to behold” (Iliad, Book III), a figure whose beauty is less a physical attribute than a force of history—one that precipitates war, rationalises violence, and becomes the alibi for male ambition. The Trojan elders, gazing upon her, do not describe complexion or feature, but effect: “Small blame that Trojans and well-greaved Achaeans should suffer so long for such a woman” (Iliad III.164–165). Homer’s Helen is not as an object of ethnography but a moral problem.

Ancient Greek myth never aspired to naturalism. Its truth was poetic and ethical, not documentary. Aristotle reminds us in the Poetics that poetry is “more philosophical and more serious than history, for poetry speaks of universals, history of particulars.” Helen belongs to this realm of universals: desire, blame, displacement, and the tragic habit of making women bear the cost of men’s wars.

The ancient Greeks themselves understood this instability. Euripides’ Helen radically reimagines her as an apparition, insisting that the woman blamed for the war “was not in Troy at all.” This is not revisionism but tradition. Greek myth was self-revising and alive to contradiction. As Jean-Pierre Vernant later observed, myth is “a way of thinking in stories,” not a closed archive. This Christopher Nolan seem to have understood very well.

Casting Helen as a Black woman will not be a departure from the myth but a continuation of its logic. It asks the same ancient question under modern conditions: Who is permitted to embody beauty without punishment? Who is blamed when empires burn?

Modern history gives this question sharper edges. Frantz Fanon wrote that “the Black body is surrounded by an atmosphere of certain uncertainty,” a body onto which fantasies, fears, and desires are projected. This observation echoes uncannily with Helen’s fate. She is less a person than a screen upon which male honour, rivalry, and imperial will are projected.

As Simone Weil wrote in her essay The Iliad, or the Poem of Force, “Force turns anybody who is subjected to it into a thing.” Helen, though spared the sword, is not spared this transformation. Weil argues that force's ultimate power is the ability to transform a human being into an inanimate object. She breaks this down into two primary forms:

In the Xhosa historical events of early nineteenth century that led to the third civil war of AmaRharhabe known as the Battle of Amalinde, aka the War Thuthula, the stunning beauty of Thuthula became a bone of contention between the regent king Ndlambe and his nephew Ngqika who had come of age to assume his throne. Though the real issues of the civil war was the throne the casus belli for the last battle was Ngqika’s abduction of his uncle’s wife, Thuthula. This lost him a following among traditional amaRharhabe who couldn’t condone the blasphemy. Thuthula, in Weil’s language, was reduced to The Living Thing by powerful men of amaRharhabe like Helen of Troy.

Nolan seems to understand also that beauty, in ancient tragedy context at least, is not an ornament but a symbol of power—and power, in tragedy, is always dangerous. By casting a Black woman as Helen, he will also be challenging the modern habit of reserving universality for white bodies alone. And insisting, instead, on what James Baldwin articulated with devastating clarity: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.” Myth survives precisely because it allows us to read ourselves into the structures of power we live in resistance or celebration of.

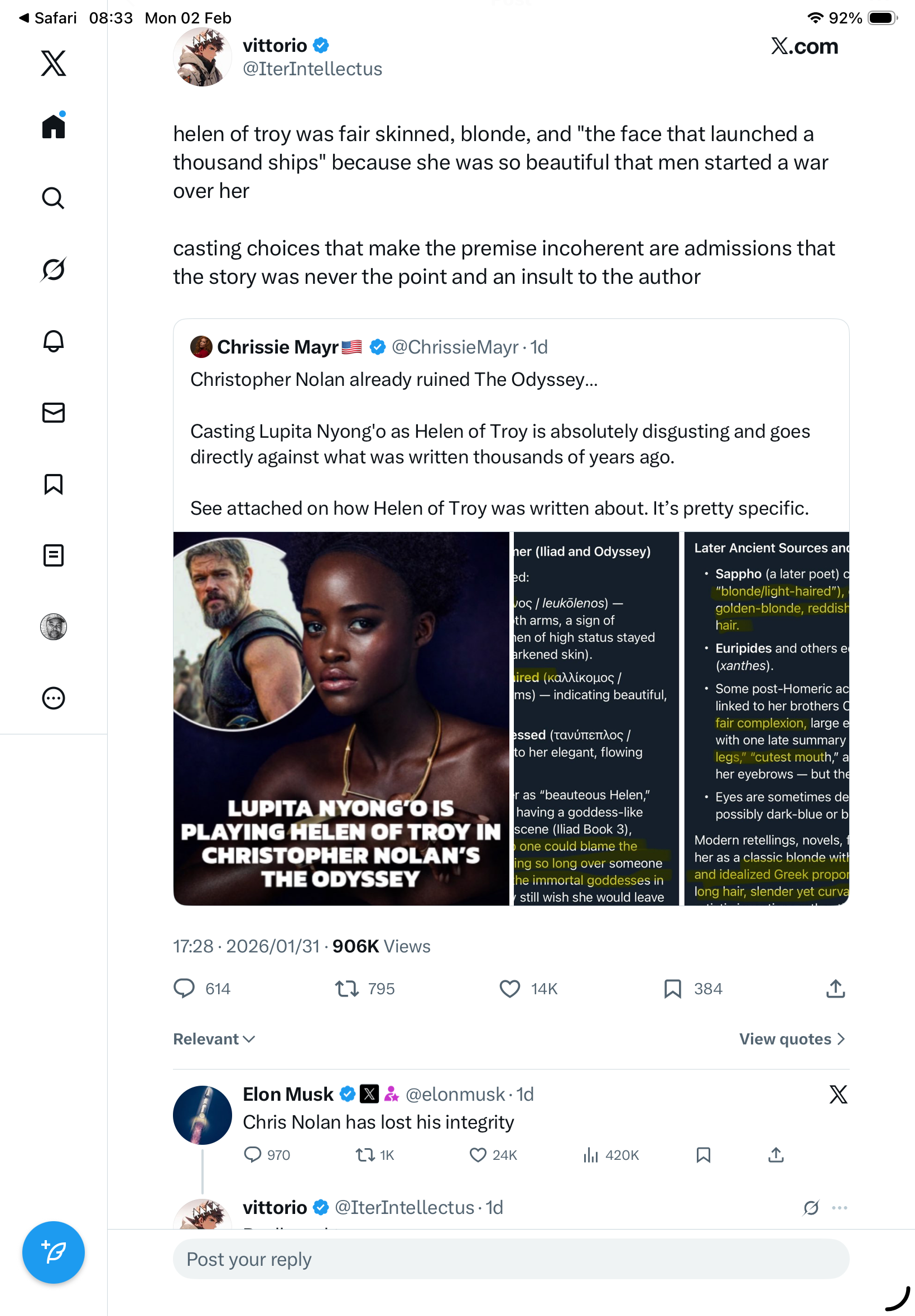

There is no evidence in Homer for Helen’s skin colour; there is overwhelming evidence for her symbolic charge. The Bronze Age Mediterranean was not a racially sealed world like ours, but a network of exchange—Mycenaean, Egyptian, Anatolian, Levantine. To impose modern racial boundaries on ancient myth is an anachronism I hope Nolan is refusing to participate on. His Helen at least, despite the myopic intellectual understanding by the likes of Elon Musk who have began to attack him, stands within Greek ancient tradition. All it demands of Helen is that she be radiant, ambiguous, intelligent, burdened by accusation, and painfully self-aware. Homer’s Helen knows history has been made her “a dog-faced thing” (Iliad VI.344).

Ultimately, I am sure the film will not be asking the audience to see Helen differently because she is Black, but to see her clearly for the first time as a human being trapped inside a myth that demands a scapegoat. What other people, if not black people, carry such a burden in our age. I hope, in a way, this would be the tragedy the movie The Odyssey will partly be staging.