BLACK HELEN OF TROY

If true the casting of a Black woman, Lupita Nyong’o, by the director Christopher

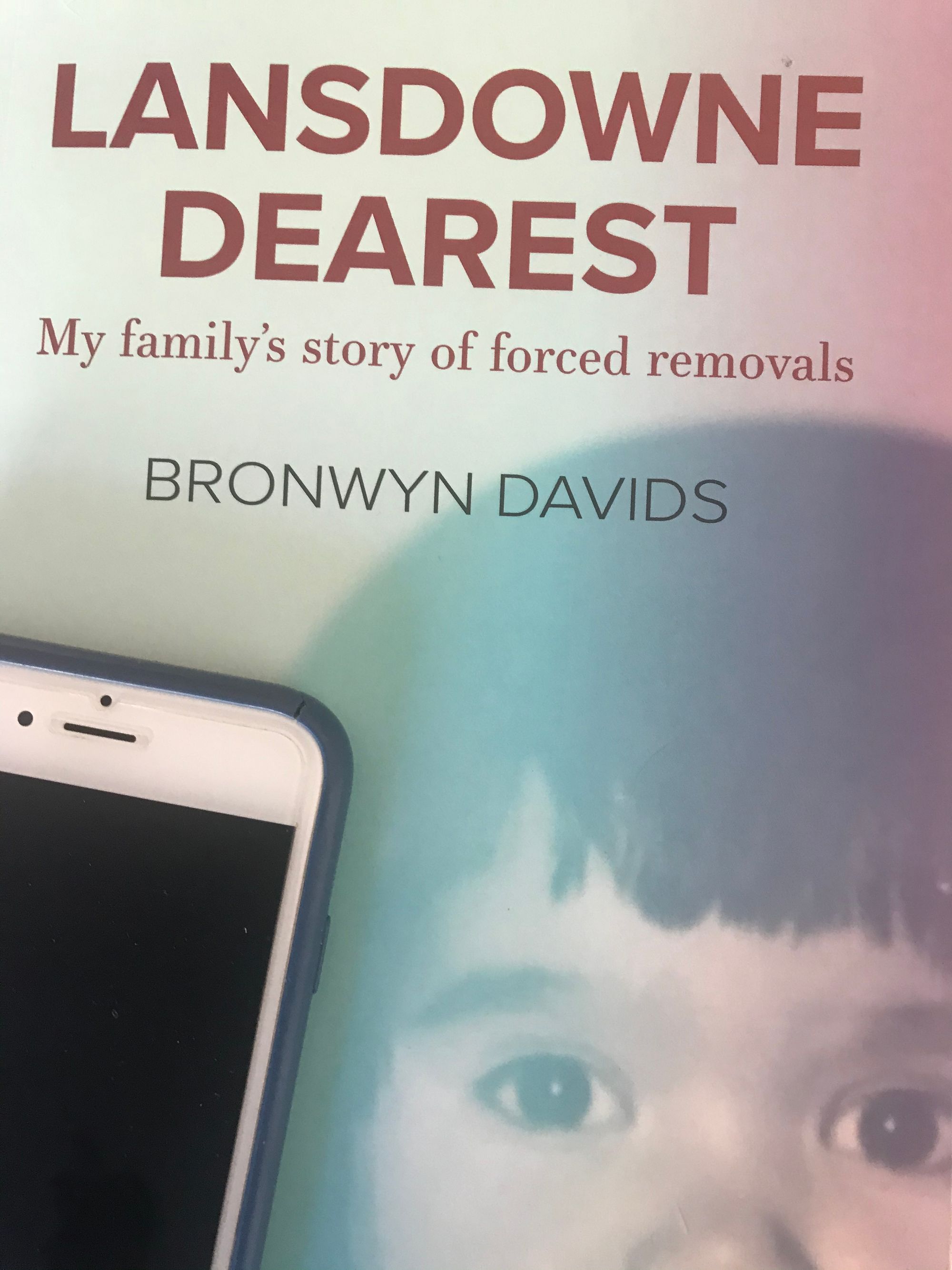

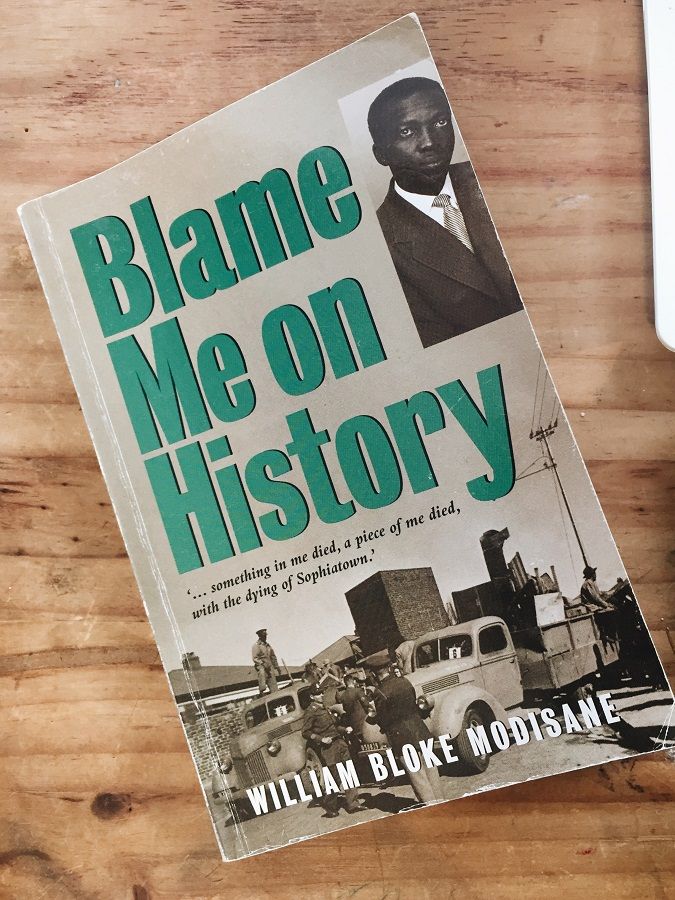

Bronwyn Davids, who used to write for the Cape Times and Cape Argus during what she calls an era of "apartheid's death watch" (from 1988 to 1992) has written a book that is a worthy inheritor to Bloke Modisane's autobiography, Blame Me On History. When Modisane moans the destruction and removals from Sophiatown Davids sing a poignant dirge for one of the neglected areas in our history of apartheid forceful removals, that of Lansdowne. Even the Cape Town people are often only aware of District Six removals but not Rondebosch, Claremont, Kenelworth and other areas, espeially these ones the Lansdowne Road traverses. The original residents of these areas were removed to make way for white suburban settlements, industrial areas and malls, including the invidious Cavendish Mall. Davids' grandfather, Joe McBain, of mixed Scottish descent, bought land there to build her family a house at Heatherely and Dale Street in 1920.

Davids writes in beautiful sparse language, often with underlying current of melancholic rapture. This is her in one of her visits to Lansdowne on the Christmas Eve of 2018:

Forlorn and chocked up, coughing from the ash of memory, I stood at the narrow windows in front of the surgery [where her home used to be], more or less on the same spot where Dor would have stood, gazing down Dale Street and seeing bulldozers demolish our old home. I felt weighed down by tremendous sadness.

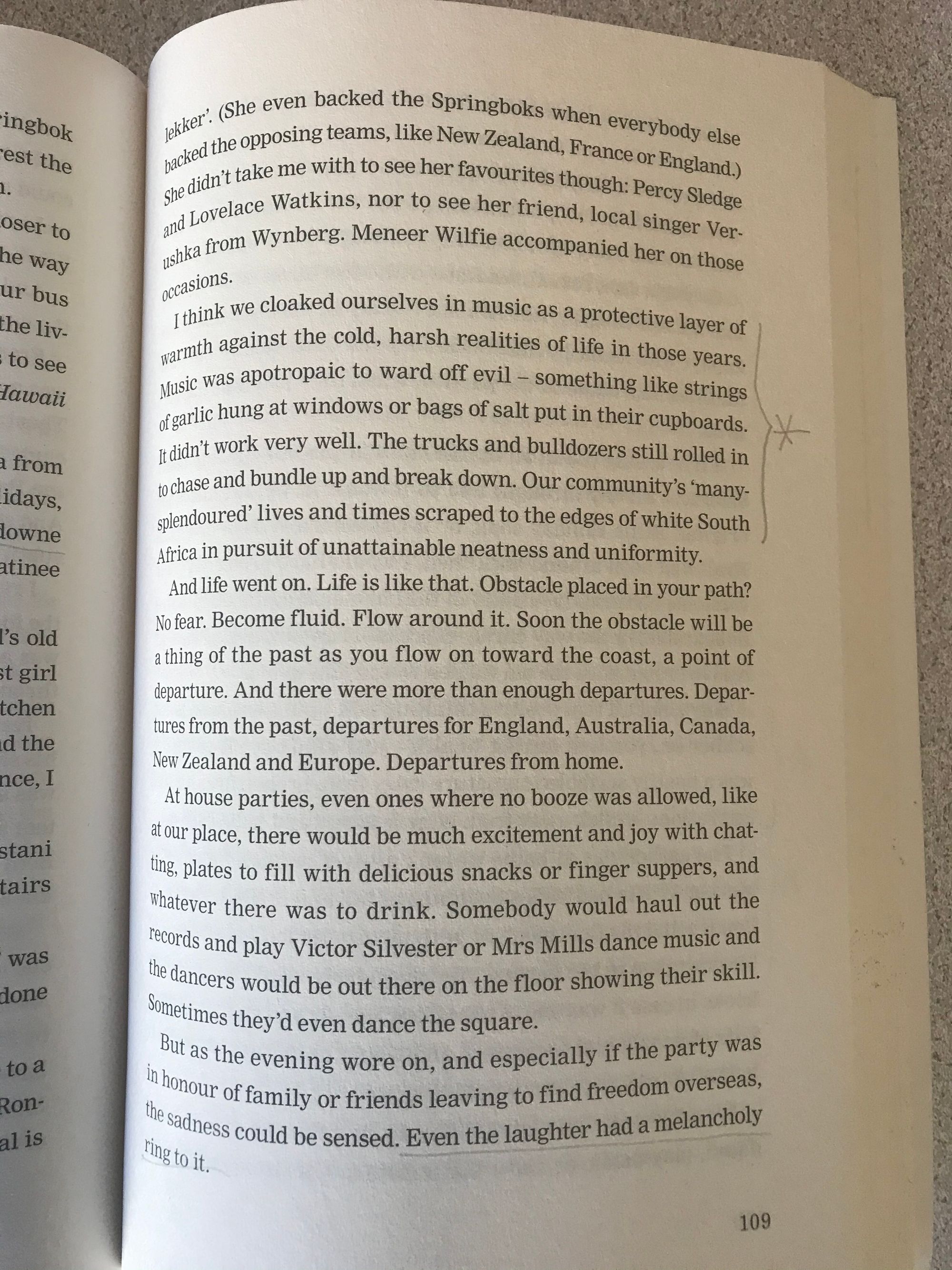

If Modisane used drama and political activism to counteract the sadness that came from the loss of their Sophiatown life for Davids religion (Catholicism) and words (journalism and literature) is what she chose to be the scaffold by which she erected her life post the ashes of Lansdowne demolishing. She takes us into confidence about the cultural issues within the Coloured communities: Colourism, Classicism and Passing (pretending to be white) before taking us through the foundations of Cape Town from the point of view of those who live in the bloated stomach of the city called the Cape Flats, behind the posh mountain belt of the tourist broacher pictures. The historical lessons abounds in this book, beginning with the evolution of coloured names, like why so many of them end with an 's' (I won't spoil your fun by revealing it) to why the townships are called Cape Flats (no its no because of flats built for black people there).

Davids uses the biographical skeleton of Joe to show us how history affects individual lives and families, from the health challenges of the Spanish Flu to the economic difficulties of the Great Depression, from the fishing opportunities of Kalk Bay to fears of Group Areas Act since the fifties. Are you old enough to remember the earthquake of 1969 that affected Tulbach most? Can you really believe the stupidity of the apartheid regime for choosing to build the Koeberg nuclear plant right on top of the earth quake Milnerton Fault line the scientists says moves every hundred years or so, meaning we're due for another tremor in, say 2069/70? What would happen then should the next tremor affect the nuclear reactors? These are just few things you learn from this wonderful memoir.

The book is written in controlled anger to convey a sense of life above tragedy, of normalcy before the cold and pitiless uprooting by the apartheid system. Davids' prose is stripped of lustre, but has a deep sense of fatigue in the ways of the world, which lends it a touch of lassitude and imputable build into the narrative of quiet tension in someone who has seen it all. As a fellow Catholic I recognise the influence of contemplative resignation on her tone. There's spiritual strength behind her dispirited dissection of suffered seasons of life. We call it the way of the lilies spirituality, espoused by the likes of Julian of Norwich that all will be well, and all manner of things shall be well.

Davids' prose is stripped of lustre, but has a deep sense of fatigue in the ways of the world, which lends it a touch of lassitude and imputable build into the narrative quiet tension of someone who has seen it all. As a fellow Catholic I recognise the influence of contemplative resignation on her tone. It is the strength behind her dispirited dissection of suffered seasons of life. We call it the way of the lilies phenomenal spirituality, the Julian of Norwich that all will be well, and all manner of things shall be well.

Listen to her again after scattering her father's ashes at Kalk Bay (a spot many of us lucky enough to live closeby there walk our bodies on as we digest the fish an chips meal we love to consume at the habour. Or when we feel burdened of our historically having supped full of horrors from the apartheid era inheritance:

Much later I would count that aged sea wall at Kalk Bay as a beauty among many in the world that I had seen on my travels. It was a point to stand and to gaze out across the vast expanse of blue or grey or turquoise or azure or green, or a mixture of all colours, to the mountains on the opposite coastline. The gaze became the point of departure from what was. A year after Ivan (her father), apartheid died in April 1994. It has yet to be buried completely...

Then the mic drops.