BLACK HELEN OF TROY

If true the casting of a Black woman, Lupita Nyong’o, by the director Christopher

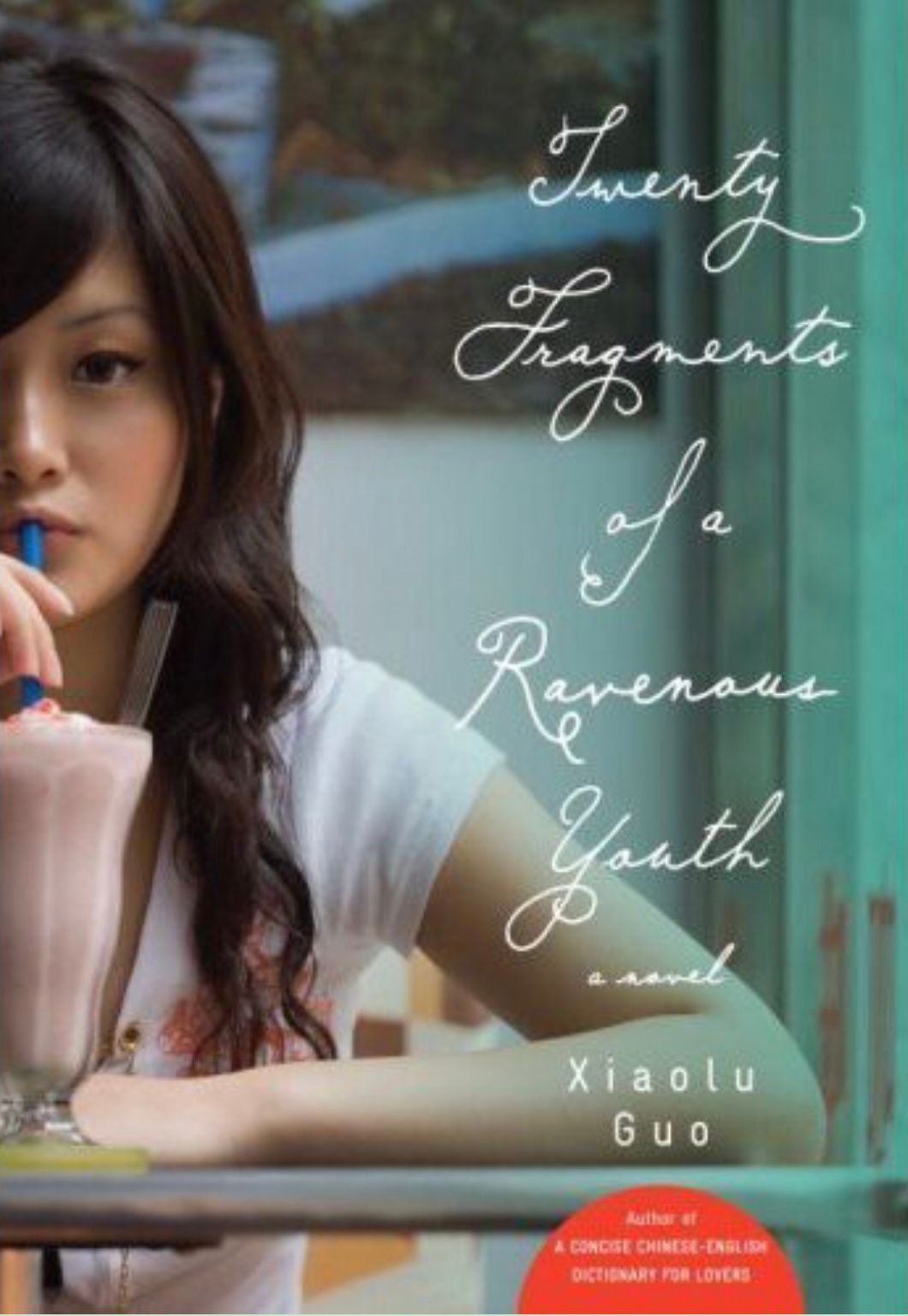

If like me you've been looking for a book with great attention to a place that'll gives you an insight into a Chinese life 20 Fragments Of A Ravenous Youth by the British novelists of Chinese descent, Xiaolu Guo, is the book for you. The writing skill of Guo is not only beautiful by she has acute observational powers that creates compelling character and a wonderful way of evoking a place to an extent that you come out from the book with a sense of life. The story is told in twenty snap chapters of cinematic quality and pictures taken from the areas of narration at the beginning of every chapter. There's immediacy and poignancy which pulsate with life, energy and sensation in the narrative voice of Fenfang.

A seventeen year old young woman, Fenfang, the protagonist of the book, fearing her future will be nothing, shakes off the dust of her Chinese village life, packs an almost empty suitcase, with nothing more than hope propulsive drive, and shoot for a city life in Beijing. As she left, her little village of sweet potato plantation is already planting memories in her mind. She looks back on it with immediate nostalgia that's rendered to us by an incantatory Baldwinan prose the narrative of the books carries through out: The hills, the fields, the well and the river – I looked at these things I was leaving and already they were becoming my memories. To my delightfully enchantment with riverbanks, the riparian reverie endures throughout the book.

She registers as an actress so she may have a profession and produce evidence for staying in the city of Beijing when she encounters Police who otherwise would deport her back to the village. We learn that it is a common thing among the rural youth China to employ similar tricks when they want to stay permanently in the Chinese's cities. Fenfang notices: There were three other girls filling out forms. They looked much cooler than me: dyed hair, tattooed arms, fake leather handbags, jeans with holes, the whole lot. They chatted and giggled like geese.

Arriving a rural greenhorn in Beijing she knows that she would not be allowed to stay in hotel even if she could afford it, and so she walks into the east side of the city to find a hostel or some place that accommodates peasant workers like herself: I ended up in the east of the city, near Bei He Yan, a Hutong area. The Hutongs. Long, thin alleys bordered by low, grey houses surrounding noisy, crammed courtyards. Countless alleys packed with countless homes where countless families lived. These old-time Beijing residents thought they were the 'Citizens of the Emperor'.

She gets hungry and decides to buy a baked potato from a street vendor. While sitting on public bench she witnesses a terrible accident of a truck that knocks over and carries away the injured mother and her child. After a while she decides to occupy their house whose door and windows were left opened for a while while she looks for a job and her own place. She finds work as an extra and a cleaner on movie sets and theaters: After each screening, I had to sweep up all the sugar-cane peels, half-eaten chicken legs, peanut shells, melon rinds and other crap that people leave behind – sometimes even fried frogs.

She moves into her own place when she's finds all sorts of pests, from the cockroaches to Neighbourhood Committee gatekeepers to nosey lift drivers who are always ready to spy on your actions and movements to report to the Party officials: The major drawback was the Neighbourhood Committee people downstairs. I couldn't stand them. In my village we used to call them old cocks and old hens. They would sit for hours in the dust, red armbands on their sleeves, serving their everlasting socialism.

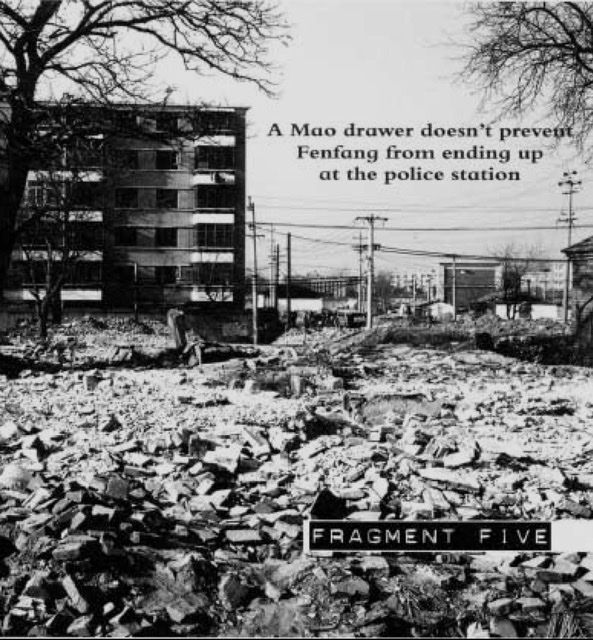

She's sometimes suspected of 'immoral acts,' like prostitution or spying for foreigners. She leaves like that from one dirty apartment to the other, trying to organise her life towards success in film industry. She also tries to develop herself by registering for short courses that boost her prestige on the industry to qualify herself also as a permanent city dweller. She keeps the certificates on what she calls her Mao Drawer, ready to be produced when evidence of self development is demanded by the officials.

What did she think of the apartments she moved into, sometimes six times in one year: THERE WERE NO CHINESE ROSES on the Chinese Rose Garden Estate, but there was plenty of rubbish. I had complicated emotions towards that place. It was like having a very ugly and smelly father, but you still had to live with him, you couldn't just move out … I've been blessed with cockroaches in every place I've lived in Beijing, but it was in the Chinese Rose Garden that I was truly anointed. My apartment was their Mecca.

On one of the sets she meets someone, Xiaolin, who is an assistant director who become her boyfriend and tormenter later. They move in together, rather she moves in with him and his family. She feels claustrophobic and eventually dumps him for an American who is doing a research for his own movie in China: If I had been thinking straight, I would have realised that Xiaolin wasn't for me. His animal sign was the rooster, and they say the monkey and the rooster don't mix. But I was young. I didn't think about the future seriously. I was just in search of those shiny things...We lived so close to each other, every millimetre of the floor was used. The two cats would pee in a sand box, but the dog always shat beside our bed. He also kept making neighbours' bitches pregnant. After three years, the grandmother was even more decrepit, and the two little sisters were getting on my nerves. There was no oxygen left in the room, I was worn out. It was like being back with the rotten sweet potatoes. I wanted to run and run and run.

The strength of this novel is in introducing us to the life of contemporary Chinese's youth living in a big city. We learn about the dust storms, the scourge of Beijing, the city of smokers that's flooded by cars in permanent fog of pollution and dust. We get to observe Chinese's cuisine, history, geography, landscape and architecture. Fenfang's fresh voice, to my regret, seems to fade as she moves up in social class, adopting habits of the learned and the monied; proving once more that poverty has a better artistic voice than affluence. I love the younger poor and struggling Fenfang more.

After a few years she visits home only to learn what most of us learn by experience that you can never go back home again: I worried that my will to survive might shrink and age here. I suddenly missed the cruel Beijing life. I missed my insecurity. I missed my unknown and dangerous future. Heavenly Bastard in the Sky, I missed the sharp edges of my life.

She goes back to her grind in Beijing only to discover she had also outgrown the city too. With a little bit money on her pocket she frequently travels in and out of the city, visiting mostmy areas of ancient historical significance in China. After ten years in Beijing she finally leaves for good: The next day, I left Beijing. I bought a one-way ticket to Shan Tou. I wanted to smell the South China Sea. One of her goals is to fulfill her ambition of becoming a writer.